OPINION:

The daily newspaper was not so long ago the king of the mountain, only to become in many places a pale, wrinkled princeling with tired blood, run over by not-so-great entertainers and pipsqueak purveyors of the shallow and the silly — and sometimes the fake — on the internet. As the president might say, “sad.”

This didn’t happen overnight. Newspapers began failing years ago with the decline of faithfulness to the facts. Journalism, to use a word once scorned as hoity-toity in most newspaper newsrooms, embraced entertainment just as the culture moved beyond literacy and the public wanted to watch moving pictures and talking heads with nothing substantial to say.

Everything sad and bad was made worse by the confluence of the 2016 election, the crowning of ignorance as political correctness, and the unexpected arrival of Donald Trump, channeling P.T. Barnum, at the White House. The old way of doing things, presided over by tough, no-nonsense editors with no tolerance for punditry on Page One, looked like not nearly as much fun as mixing it up in the process of the political.

The New York Times, which once almost lived up to its famous slogan of reporting “all the news that’s fit to print,” found that printing all the news that fits its politics and its prejudices was more rewarding. In a remarkably candid interview, Dean Baquet, the executive editor of The Times, decreed that the struggle for fairness in the newsroom is over.

“I think that [Mr.] Trump has ended that struggle,” he told Ken Doctor of the Neiman Lab, a trade publication. “I think we now say stuff. We fact-check him. We write it more powerfully that it’s false.

“I think he gave us courage, if you will. I think he made us — forced us — because he does it so often, to get comfortable with saying something is false.”

Jim Rutenberg, the media reporter for the newspaper, declared in a column last year that most reporters saw [Mr.] Trump “as an abnormal and potentially dangerous candidate,” and concluded that the reporters have a duty to be “true to the facts.” The facts, as he did not say, are the facts in the opinion of the reporters.

One editor who is definitely not comfortable with saying something that’s false, is Gerard Baker of The Wall Street Journal, the nation’s largest newspaper with an influence stretching far beyond its origins on Wall Street. Dean Baquet’s newspaper is currently trying to pick a fight with Mr. Baker over his reluctance to get comfortable with New York Times journalism.

The Times reported remarks that Mr. Baker made to a meeting with his staff early this year, when some of the reporters complained they were restrained from imparting their “toughness and verve” to the reporting on politics and President Trump.

“We can’t allow ourselves to be dragged into the political process, to be a protagonist in the political fight,” Mr. Baker told his staff. Americans, he said, hold a deep distrust of the media, and if his newspaper covered Mr. Trump in an overly confrontational way that mistrust would increase.

The New York Times deduced from that that Mr. Baker would not join the campaign of the righteous and correct to inject opinion and advocacy into its coverage of the news. That’s why The Times is trying now to light a fire under Mr. Baker.

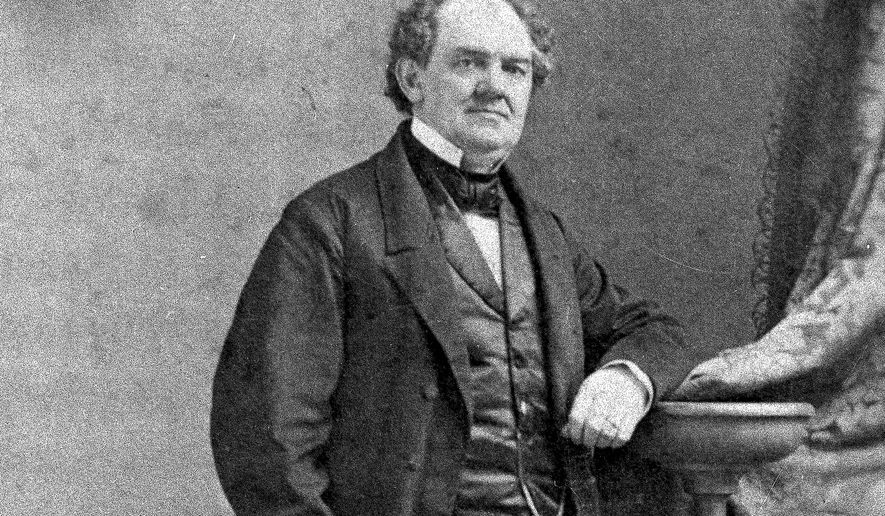

The Journal’s fidelity to facts was a gift from the man who built the modern Journal, Barney Kilgore, who took it over when it was a trade journal with just a tiny readership on Wall Street, and set down a formula of delivering “a fact a line, every line of type must contain at least one fact.” The reporter’s opinion was not welcome. The Journal became the most carefully edited newspaper in the country. [Full disclosure: I worked for 13 years on the old National Observer, covering civil rights, politics and the war in Vietnam, a sister paper of The Wall Street Journal.]

The New York Times was not always a purveyor of a new and unworthy journalism. It proposed in 1967 to publish an afternoon edition it would call The Evening Times. The idea lasted only through two prototype editions only for a closet shelf, but it left what was to be an eloquent founding statement, promising “fresh news, competitive and candid. We will not poke our fingers in people’s eyes simply because our presses give us the power to do so. But we will work every day, to the best of our energies, to strip away cant and protective foliage around the news.”

Mr. Baquet should read that to his staff, if only for laughs.

• Wesley Pruden is editor in chief emeritus of The Washington Times.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.