Eamonn Keane

From the personhood of animals to infanticide and bestiality: the ethical relativism of Peter Singer

By Eamonn Keane

Introduction

I was reworking an essay I had published in Australia some years ago on Peter Singer's ethical relativism when there arrived Matt Abbott's latest column in RenewAmerica headed 'Animal rights' versus good stewardship' (May 18, 2010). As the Introduction to bioethicist Wesley J. Smith's latest book — A Rat is a Pig is a Dog is a Boy: The Human Cost of the Animal Rights Movement — which Abbott has inserted in his column indicates, Singer is one of the intellectual founders of the animal rights movement. In what follows I endeavour to show that the barbarous propositions that Singer's ethical system concludes to is intrinsically linked to his atheistic understanding of reality.

Revolt Against God

It is becoming ever more evident that the greatest crisis in Western societies today is a crisis of religious and moral perceptions. In his highly acclaimed essay Revolt Against God: America's Spiritual Despair, William Bennett argued that by most measures of civilised morality the United States had become an increasingly decadent society. He stated that the only way out of the moral and cultural quagmire was through a return to religion which would provide the basis for a rediscovery of virtue and moral vision. Bennett noted that social regression and exploding rates of crime in the United States were accompanied by "a disturbing reluctance in our time to talk seriously about matters spiritual and religious." He added that perhaps all of this had something "to do with the modern sensibility's profound discomfort with the language and the commandments of God."

The moral failings of the West stem from a runaway pluralism which sees practically all beliefs and lifestyles as possessing equal moral value. Despite the many enigmas that punctuate its history, Western civilisation thrived on a consensus based on the Judeo-Christian vision whereby the vocation of the human person was seen as a call to freedom understood as the ability to carry out one's duty towards God and neighbour.

The shape of the Western world today has been heavily influenced by certain intellectual currents which have sought to liberate human consciousness from all dependence upon God. In this setting, the human person is no longer recognised as a being made in the image and likeness of God, but is instead reduced to the status of an educated ape. In consequence of this reductionism, it is asserted that there is no created human nature that bespeaks an objective and universal moral law. As Solzhenitsyn pointed out in his famous Harvard address in 1978, it was this rebellion against God and the moral law that lay at the heart of the oppressive ideologies of recent centuries such as secular liberalism, communism and national socialism. Common to these ideologies is the belief that one can be good and virtuous without God.

Utilitarianism: From Bentham to Singer

Singer is an Australian philosopher who was the first President of the International Association of Bioethics. He was the Ira W. DeCamp Professor of Bioethics, University Center for Human Values, Princeton University 1999-2004 where he now works part-time, as well as being a Professor at the University of Melbourne's Centre for Applied Philosophy and Public Ethics. He has also authored the ethics section for the current edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica.

The ethical system Singer adheres to is known as utilitarianism. The term 'utilitarianism' is derived from the Latin word utilis which means useful. In general, utilitarians do not accept that actions are good or bad in themselves, but rather that their moral evaluation depends on how they produce increases or decreases in the amount of happiness in life. Utilitarians often equate happiness with the satisfaction of the desire for pleasure, and pain with its frustration. In contrast to this, Aristotle posited that the virtuous person finds pleasure only in what is good and is willing to embrace pain for a good end. In the same vein, St. Thomas Aquinas pointed out that when St. Augustine approved the statement "happy is he who has all he desires," he was careful to add the words "provided he desires nothing amiss." [1]

Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) is regarded as the father of utilitarianism, which he expounded in his Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation. According to Bentham, an action is right if its performance will be productive of an increase in happiness or a reduction in pain. Otherwise it is to be judged wrong. While his ethical philosophy became known as utilitarianism, Bentham himself preferred to call it "the greatest happiness principle" since it is based on the idea that the ethical goal of all behaviour should be the generation of the maximum possible amount of happiness for all conscious beings. Hence he stated that the "fundamental axiom" of "right and wrong" is the attainment of "the greatest happiness of the greatest number." [2] In Bentham's ethical system, "happiness" and "pleasure" are synonymous terms that are understood in a broad sense as having intellectual, physical, moral and social dimensions. Due to its emphasis on the maximisation of pleasure and the minimisation of pain, Bentham's utilitarianism has often been referred to as "ethical hedonism."

One of the problems associated with utilitarianism concerns the definition of 'happiness' and its attainability. In what does happiness consist? Is it attainable in this life or in life after death? Can the reduction of moral philosophy to the determination of how to maximise individual or societal happiness be reconciled with the need to recognise universal and objective moral principles? Should happiness be viewed only as a consequence of the performance of unconditional duties? Speaking of the problems occasioned by the nebulous meaning the term "happiness" can have, Mortimer J. Adler said: "It may be granted that there are in fact many different opinions about what constitutes happiness, but it cannot be admitted that all are equally sound without admitting a complete relativism in moral matters." [3]

Plato identified happiness with an inner peace and harmony in the soul. Socrates understood happiness in relation to virtue. He said "the happy are made happy by the possession of justice and temperance and the miserable by the possession of vice." [4] Aristotle defined happiness as "activity in accordance with virtue." [5] He drew a distinction between intellectual virtue and moral virtue giving greater weight to the latter. He taught that a morally virtuous person finds pleasure in doing good. He held that there existed universal and objective moral truths which give rise to the natural moral law. He said: "There is in nature a common principle of the just and unjust that all people in some way divine [discern], even if they have no association or commerce with each other." [6]

In Christian belief, the desire for happiness is of divine origin: "God has placed it in the human heart in order to draw man to the One who alone can fulfill it...God alone satisfies." [7] Here, the perfection of happiness is arrived at through our entry into eternal life with God in Heaven. However, happiness in this earthly life is attainable to the extent that we model our lives on Jesus Christ and seek to live a virtuous life. This includes obedience to the Ten Commandments and all that they entail. Coupled with this, the Beatitudes "respond to the natural desire for happiness," and they "reveal the goal of human existence, the ultimate end of human acts" — which is to share in God's "own beatitude." [8]

Apart from Bentham's ethical hedonism, there are many other varieties of utilitarian thought, such as Robert Goodwin's rule utilitarianism and Peter Singer's preference utilitarianism. Sometimes utilitarianism is referred to as consequentialism, insofar as actions are to be judged good or bad according to their consequences. Singer says that his brand of utilitarianism differs from its classical form in that "best consequences" are understood "as meaning what, on balance, furthers the interests of those affected, rather than merely what increases pleasure and reduces pain." [9] Having said this, however, Singer adds that if we interpret classical utilitarians like Bentham to have used the terms "pleasure" and "pain" in a broad sense so as to "include achieving what one desired" as a "pleasure" and the reverse as "pain," then "the difference between classical utilitarianism" and his own based on interests "disappears.." [10]

Utilitarianism is a form of materialism in that it is focused on immediacy and efficiency in achieving a form of happiness that is confined to this life only. In conjunction with this, the notion of maximising 'utility' (happiness) is laden with ambiguity. For example, since maximising utility implies a comparison of the value of the utility of all forgone alternatives, then how can there ever be enough time to calculate the total opportunity cost in terms of utility forgone as a consequence of choosing one option in preference to another? Further to this, how do we account for those effects of our actions on societal 'happiness' that we are not aware of?

In pointing to utilitarian ethics as a product of the English Enlightenment, which tended to forget the human element in morality, Professor William K. Kilpatrick said:

As a moral philosophy, utilitarianism is defective because it postulates that ends justify means and it easily ends up counting as 'pleasurable' and good whatever is the object of desire. To this end, "it tends to regard freedom as the unrestricted exercise of one's self interest," and the satisfaction of one's desires to be "limited only by the proviso that it doesn't infringe the same freedom of others." [13] As such, "it is a receipe for license rather than true liberty and tends to lead to further enslavement as is shown, for example, by the unrestricted use of drugs or alcohol or sexuality." [14]

While we should not minimise the role of motives and circumstances in morality, [15] the morality of the human act depends nevertheless "primarily and fundamentally on the 'object' rationally chosen by the deliberate will." [16] The object of an act refers to its matter — whether or not it is good or evil in itself. In this regard, there exist "moral absolutes" which means that there are objects of human choice which are always and everywhere morally bad. Such actions, referred to as "intrinsically evil," include bestiality and the deliberate killing of babies. In contrast to this, a major objection to utilitarianism is that "it does not allow a statement to the effect that some actions are intrinsically or absolutely good or bad: they are only better or worse than others." [17]

The utilitarian calculus cannot account adequately for the demands of justice, nor does it take into account the nature of desires seeking to be satisfied. For example, the intention to kill an innocent human being is to desire to commit an intrinsically evil act and is thus a disorder of the will. A person intent on performing such an action should be restrained, irrespective of how he or she hopes to increase individual or societal happiness. This, at least, has been a foundational principle of all civilised societies.

Influenced by Joseph Fletcher

Apart from classical utilitarians like Bentham, Singer has also drawn on the ideas of Joseph Fletcher in developing his ethical system. Fletcher, who is regarded as the father of Situation Ethics, was an Episcopalian priest who died in 1991 at the age of 86. In 1960, Fletcher renounced his belief in God but remained a priest because he found the Episcopalian Church useful for advancing his ideas. He was pro-abortion and pro-euthanasia, being an advocate of "mercy-killing" and a member of the board of directors of the Euthanasia Council (now called 'Choice in Dying'). His writings had a futuristic aspect to them in that he spoke approvingly of fetal experimentation and the possibility of manufacturing human beings. Fletcher's wife of 60 years, Forrest Hatfield, worked closely with Margaret Sanger (1883-1966), who was the founder and first president of the International Planned Parenthood Federation, which is now the biggest promoter of abortion world-wide.

Singer draws on Fletcher's personal criterion (which he refers to as 'indicators of personhood') to establish a demarcation line between those human beings who he thinks should be granted the status of personhood and those who should not. In this regard, he lists Fletcher's indicators of personhood as "self-awareness, self-control, a sense of the future, a sense of the past, the capacity to relate to others, concern for others, communication, and curiosity." [18] Interestingly, Singer makes no mention of the fact that Fletcher also included an IQ of greater than 40 as one of his indicators of personhood.

Personhood is Not Inherent in the Human Being

Asserting that personhood is not something inherent to every human being but is contingent on the development of self-consciousness, Singer says: "I propose to use 'person' in the sense of a rational and self-conscious being." [19] On this basis, he distinguishes between two types of members of Homo sapiens — those who are 'persons' and those who are not. He says that an essential qualification for the status of personhood is that a being "be capable of anticipating the future, of having wants and desires for the future." [20] Having thus defined away the personhood of some human beings who for various reasons may not measure up to his criterion of personhood, Singer then boldly asserts that "it is reasonable to say that only a person has a right to life." [21]

Singer's 'New Commandments': Kill the Child if it makes life easier for you

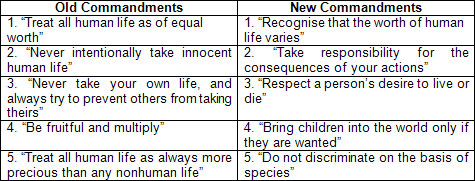

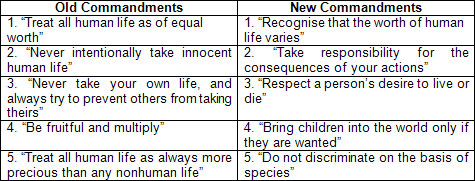

When Singer's utilitarianism is combined with his assertion that personhood is contingent on the possession of exercisable cognitive abilities, what we end up with is a "deathly" cocktail. He holds that the sanctity of life ethic is "terminally ill" in that its claim that all human life has some special dignity or worth "crumbles" when "challenged." He intones that this "traditional ethic" is defended "by bishops and conservative bioethicists...who speak about the intrinsic value of all human life, irrespective of its nature or quality." [22] In place of the sanctity of life ethic, Singer proposes a new one which is replete with five "New Commandments," which he says are necessary alternatives to the five "Old Commandments." The table below shows these two sets of commandments as Singer formulates them: [23]

Singer argues that the selective killing of infants should be permissible, as should other forms of euthanasia and assisted suicide. In regard to the question of killing, he says: "When we consider how serious it is to take a life, we should look, not at the race, sex or species to which that being belongs, but at the characteristics of the individual being killed, for example, its own desires about continuing to live, or the kind of life it is capable of living." [24]

Consistent with his belief that "there could be a person who is not a member of our species," and that "there could also be members of our species who are not persons," [25] Singer asserts that in order "to avoid speciesism we must allow that all beings who are similar in all relevant respects have a similar right to life — and mere membership in our own biological species cannot be a morally relevant criterion for this right." [26] After stating that "there will surely be some nonhuman animals whose lives, by any standard, are more valuable than the lives of some humans," Singer goes on to say: "A chimpanzee, dog, or pig, for instance, will have a higher degree of self — awareness and a greater capacity for meaningful relations with others than a severely retarded infant or someone in a state of advanced senility. So if we base the right to life on these characteristics, we must grant these animals a right to life as good as, or better than, such retarded or senile humans." [27]

In regard to abortion, Singer argues that "an abortion late in pregnancy for the most trivial reasons is hard to condemn unless we also condemn the slaughter of far more developed forms of life for the taste of their flesh." [28] After saying that the fetus is not a person and hence its life "is of no greater value than the life of a nonhuman animal at a similar level of rationality, self-consciousness, awareness, capacity to feel etc," Singer goes on to add that "it must be admitted that these arguments apply to a newborn baby as much as to a fetus." [29] Consistent with this position, Singer asserts that "the grounds for not killing persons do not apply to newborn infants" since "newborn babies cannot see themselves as beings who might or might not have a future." [30]

Regarding Singer's assertion that unborn babies and infants are not persons because they lack certain exercisable cognitive abilities, Professor William May says that this is "fallacious" because "it fails to distinguish between a radical capacity or ability and a developed capacity or ability." Explaining this distinction, Professor May says:

Singer says that the "present absolute protection of the lives of infants is a distinctively Christian attitude rather than a universal ethical value." He states that "infanticide has been practised in societies ranging geographically from Tahiti to Greenland and varying in culture from the nomadic Australian aborigines to the sophisticated urban communities of ancient Greece or mandarin China." [34] He holds that these cultures "were on good ground" insofar as they "practiced infanticide." [35] Singer even gives a Malthusian twist to his discussion of infanticide. He says that "in the case of infanticide, it is our culture that has something to learn from others, especially now that we, like them, are in a situation where we must limit family size." [36] Obviously, Singer hasn't yet caught up with the now widely acknowledged fact that the only demographic problem in Western countries is declining fertility rates and aging populations.

At times, Singer packages his more controversial propositions in soothing terms. For example, in reference to infanticide he says: "We should certainly put very strict conditions on permissible infanticide; but these restrictions might owe more to the effects of infanticide on others than on the intrinsic wrongness of killing an infant." [37] However, one columnist, George F. Will, caught the barbaric "logic" of Singer's ethical system well in a Newsweek article when he said:

Indeed, Singer himself admits the arbitrary nature of his position. He says that it is "difficult to say at what age children begin to see themselves as distinct entities existing over time." He adds that "even when we talk with two and three-year-old children, it is usually very difficult to elicit any coherent conception of death, or of the possibility that someone — let alone the child herself — might cease to exist." [39] Nevertheless, Singer still insists that a "line" can be drawn on one side of which the child dies while on the other he lives. He says: "Of course, where rights are at risk, we should err on the side of safety. There is some plausibility in the view that, for legal purposes, since birth provides the only sharp, clear, and easily understood line, the law of homicide should continue to apply immediately after birth." However, he follows up this statement by saying: "Since this is an argument at the level of public policy and the law, it is quite compatible with the view that, on purely ethical grounds, the killing of a newborn infant is not comparable to the killing of an older child or adult." [40] Then, to make provision for those parents whose "preference" is that their disabled child be murdered, Singer says: "It is, however, worth considering another possibility: that there should be at least some circumstances in which a full legal right to life comes into force not at birth, but only a short time after birth — perhaps a month." [41]

Note, how in the last sentence quoted above, Singer speaks only of infants acquiring a "legal right to life," thereby denying that they possess an inalienable right to life. Singer cannot grant any infant an inalienable right to life since he has already defined all infants as non-persons and asserted that "it is reasonable to say that only a person has a right to life." [42]

In arguing for the right of parents and doctors to kill handicapped infants, Singer offers a rather specious reply to the charge that the presence of such licensed killers in a given society would greatly threathen the sense of security felt citizens thus reducing their "total amount of happiness." He says: "[No] one capable of understanding what is happening when a newborn baby is killed could feel threatened by a policy that gave less protection to the newborn than to adults. In this respect Bentham was right to describe infanticide as 'of a nature not to give the slightest inquietude to the most timid imagination.' Once we are old enough to comprehend the policy, we are too old to be threatened by it." [43]

In is meanderings through the thickets of evil abstraction, Singer fails to account for the fact that many people know and feel themselves so bound in solidarity to their handicapped brothers and sisters as to feel great 'pain" and anguish at even the suggestion that disabled infants be put to death.

Nazism Revisited

It is interesting to note that many of Singer's more notorious proposals are directed at severely disabled children since this was also the group the Nazis first targeted for euthanasia. Singer rejects any suggestion that his ethical system would have sat comfortably with the Nazi tyrants. In arguing that his pro-euthanasia position is different in essence to its Nazi counterpart, Singer says: "The Nazi 'euthanasia' program was not 'euthanasia' at all. It did not seek to provide a good death for human beings who were leading a miserable life. It was aimed at improving the quality of the Volk and eliminating the burden of caring for 'social ballast' and feeding 'useless' mouths." [44] The first thing to note about Singer's statement here is that he does not condemn the Nazi euthanasia program per se, but rather he faults it only on the motivation he believes inspired it.

The Nazi euthanasia program is partly accounted for by the fact that Singer-like utilitarian ideas began to gain currency in Germany during the early decades of the 20th century. In 1920, well before Hitler came to power in Germany, a very influential book titled Permission to Destroy Life Unworthy of Life was published. Co-authored by Karl Binding, a law professor, and Alfred Hoche, a physician, this work asserted that killing certain categories of people was a form of compassionate and "healing treatment." Regarding the influence of Binding's and Hoche's work, as well as the section following on Hitler and Baby Knauer, I will be draw heavily on an excellent article by Wesley J. Smith titled Peter Singer Gets A Chair available at www.frontpagemag.com/archives/academia/smith10-22-98.htm.

Those deemed eligible for the "compassionate treatment" Binding and Hoche wanted to mete out to them included the terminally ill and the cognitively disabled. The first category mentioned here, the terminally ill, are the category for whom Singer would legalise voluntary euthanasia. The second category, the cognitively disabled, are those Singer has defined as "non-persons," the killing of whom is "very often...not wrong at all." [45]

Binding and Hoche based their advocacy of euthanasia on the perceived misery of the mentally disabled, as well as on the costs to their families and society of looking after them — something which is echoed in Singer's utilitarian premise that it should be permissible to kill "non-persons" whose lives are deemed "not worth living," and whose death will lead to an increase in the "total amount of happiness."

The publication of Permission to Destroy Life Unworthy of Life sparked discussion among the German intelligentsia as a result of which pro-euthanasia ideas which were once regarded as abhorrent now began to win greater acceptance. Then a 1925 survey of German parents with mentally disabled children revealed that 74 percent of them would have agreed to the painless killing of their children. Hence, when the Nazis looked for the right moment to begin implementing their euthanasia program, an atmosphere sympathetic to it already existed in consequence of the prior dissemination of Singer-like utilitarian ideas.

One of the first people murdered in the Nazi euthanasia program was a child named Baby Knauer, who in 1938 or 1939 was born blind with one arm and one leg missing. Baby Knauer's father felt unable to cope with his disabled son, so he wrote to Hitler seeking permission to have the child put to death. Seeing in this request the opportunity to launch his euthanasia program, Hitler sent Dr. Karl Rudolph Brandt to examine Baby Knauer. Brandt, who at Nuremberg was condemned to death for crimes against humanity, had been given instructions that if Baby Knauer was as disabled as his father made out, then doctors could kill him. Subsequently, Brandt witnessed the killing of Baby Knauer and reported back to Hitler. This incident convinced Hitler that the time was right to introduce his euthanasia program. Thus, in 1939, he sent a note to chancellery officials extending "the authority of physicians" so that "a mercy death may be granted to patients who according to human judgement are incurably ill." [46]

The justification that was used to murder Baby Knauer is essentially the same as Singer uses when arguing that parents should have the right to have their disabled children put to death so that they themselves and any subsequent children they may have might experience an increase in "the total amount of happiness."

Concluding Remarks: From Atheism to Bestiality

A fundamental cause of radical differences in ethical perceptions is that different ethical systems have different starting points — which is to say, they differ in fundamental assumptions. The starting assumptions in any chain of reasoning determine its character and its conclusions. In this regard, all ethical systems rely on a particular anthropology which dictates its line of development.

Christian anthropology holds that God created man in his own image and likeness, that he endowed him with freedom and intelligence, and that he appointed him steward over the rest of physical creation. [47] Being so constituted, human beings are able to know the difference between good and evil and to choose between them. The dignity of the human person lies in his ability to choose the good and the institutions and laws of society should assist him in doing so. In consequence of all this, the human person is the subject of inalienable human rights and corresponding duties. First among those rights is the right to life itself. This right to life of all innocent human beings must be guaranteed at law since it is inherent to the nature of the human person and not conferred by society.

In his encyclical Evangelium Vitae (Gospel of Life), Pope John Paul II said: "By living 'as if God does not exist,' man not only loses sight of the mystery of God, but also of the mystery of the world and the mystery of his own being" (n. 22) He added that "the eclipse of the sense of God and of man inevitably leads to a practical materialism, which breeds individualism, utilitarianism and hedonism" (n. 23). In this, said Pope John Paul, "we see the permanent validity of the words of the Apostle: 'And since they did not see fit to acknowledge God, God gave them up to a base mind and to improper conduct' (Rom 1:28)" (ibid.)

Singer underpins his ethical system with an atheistic anthropology in which he asserts that there is no significant difference between human beings and animals such as baboons and pigs. In publicly declaring his atheism, he says: "I don't believe in the existence of God, so I also reject the idea that each human being is a creature of God. It's as simple as that." [48] In line with this, he accuses "the Judeo-Christian tradition" of having "an unjustifiable bias in favour of human beings qua human beings." [49] He says "the fact that animals are not members of our species is, in itself, no more morally relevant than the fact that a human being is not a member of my race or not a member of my sex." [50]

Singer says that "we should reject the doctrine that places the lives of members of our species above the lives of members of other species," adding that "some members of other species are persons: some members of our own species are not." [51] Following this proposition through to its logical conclusion, Singer asserts that "no objective assessment can support the view that it is always worse to kill members of our species who are not persons than members of other species who are." [52]

Given Singer's starting points, it is not surprising to find that in a March 31, 2001 article in the Sydney Morning Herald titled "Animal-Sex Philosopher Brings Out The Beast In The Americans," Singer is quoted as having stated at the time that sex with animals "is not an offence to our status and dignity as human beings." The article was reporting on a favourable review Singer had written of a book titled Dearest Pet by Midas Dekker which condoned bestiality. The article said that Singer speculates that the reason why most people have a revulsion of bestiality "stems from the Judeo-Christian view of a gulf separating humans from animals."

Being rooted in atheistic perceptions of reality, Singer's ethical system is incapable of defending human dignity. His defense of infanticide and bestiality serves well to illustrate the truth of the statement commonly attributed to Dostoevsky: "If God does not exist, everything is permissible." While this sentence does not, to my knowledge, appear in any of Dostoevsky's novels that have been translated into English, it can nevertheless be regarded as an accurate summation of the belief held by Ivan Karamazov in the early chapters of The Brothers Karamazov where he pretends to conclude that there is no God. While he does not speak directly the sentence quoted above, he does however assert in several places that without God "everything is lawful." Equally insightful, in another place he says: "If there is no immortality, there is no virtue."

Despite the many nuances he introduces into his work to distinguish it from classical utilitarianism, Singer's atheistic system is for all practical purposes just another form of "ethical hedonism."

NOTES:

© Eamonn Keane

May 18, 2010

Introduction

I was reworking an essay I had published in Australia some years ago on Peter Singer's ethical relativism when there arrived Matt Abbott's latest column in RenewAmerica headed 'Animal rights' versus good stewardship' (May 18, 2010). As the Introduction to bioethicist Wesley J. Smith's latest book — A Rat is a Pig is a Dog is a Boy: The Human Cost of the Animal Rights Movement — which Abbott has inserted in his column indicates, Singer is one of the intellectual founders of the animal rights movement. In what follows I endeavour to show that the barbarous propositions that Singer's ethical system concludes to is intrinsically linked to his atheistic understanding of reality.

Revolt Against God

It is becoming ever more evident that the greatest crisis in Western societies today is a crisis of religious and moral perceptions. In his highly acclaimed essay Revolt Against God: America's Spiritual Despair, William Bennett argued that by most measures of civilised morality the United States had become an increasingly decadent society. He stated that the only way out of the moral and cultural quagmire was through a return to religion which would provide the basis for a rediscovery of virtue and moral vision. Bennett noted that social regression and exploding rates of crime in the United States were accompanied by "a disturbing reluctance in our time to talk seriously about matters spiritual and religious." He added that perhaps all of this had something "to do with the modern sensibility's profound discomfort with the language and the commandments of God."

The moral failings of the West stem from a runaway pluralism which sees practically all beliefs and lifestyles as possessing equal moral value. Despite the many enigmas that punctuate its history, Western civilisation thrived on a consensus based on the Judeo-Christian vision whereby the vocation of the human person was seen as a call to freedom understood as the ability to carry out one's duty towards God and neighbour.

The shape of the Western world today has been heavily influenced by certain intellectual currents which have sought to liberate human consciousness from all dependence upon God. In this setting, the human person is no longer recognised as a being made in the image and likeness of God, but is instead reduced to the status of an educated ape. In consequence of this reductionism, it is asserted that there is no created human nature that bespeaks an objective and universal moral law. As Solzhenitsyn pointed out in his famous Harvard address in 1978, it was this rebellion against God and the moral law that lay at the heart of the oppressive ideologies of recent centuries such as secular liberalism, communism and national socialism. Common to these ideologies is the belief that one can be good and virtuous without God.

Utilitarianism: From Bentham to Singer

Singer is an Australian philosopher who was the first President of the International Association of Bioethics. He was the Ira W. DeCamp Professor of Bioethics, University Center for Human Values, Princeton University 1999-2004 where he now works part-time, as well as being a Professor at the University of Melbourne's Centre for Applied Philosophy and Public Ethics. He has also authored the ethics section for the current edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica.

The ethical system Singer adheres to is known as utilitarianism. The term 'utilitarianism' is derived from the Latin word utilis which means useful. In general, utilitarians do not accept that actions are good or bad in themselves, but rather that their moral evaluation depends on how they produce increases or decreases in the amount of happiness in life. Utilitarians often equate happiness with the satisfaction of the desire for pleasure, and pain with its frustration. In contrast to this, Aristotle posited that the virtuous person finds pleasure only in what is good and is willing to embrace pain for a good end. In the same vein, St. Thomas Aquinas pointed out that when St. Augustine approved the statement "happy is he who has all he desires," he was careful to add the words "provided he desires nothing amiss." [1]

Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) is regarded as the father of utilitarianism, which he expounded in his Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation. According to Bentham, an action is right if its performance will be productive of an increase in happiness or a reduction in pain. Otherwise it is to be judged wrong. While his ethical philosophy became known as utilitarianism, Bentham himself preferred to call it "the greatest happiness principle" since it is based on the idea that the ethical goal of all behaviour should be the generation of the maximum possible amount of happiness for all conscious beings. Hence he stated that the "fundamental axiom" of "right and wrong" is the attainment of "the greatest happiness of the greatest number." [2] In Bentham's ethical system, "happiness" and "pleasure" are synonymous terms that are understood in a broad sense as having intellectual, physical, moral and social dimensions. Due to its emphasis on the maximisation of pleasure and the minimisation of pain, Bentham's utilitarianism has often been referred to as "ethical hedonism."

One of the problems associated with utilitarianism concerns the definition of 'happiness' and its attainability. In what does happiness consist? Is it attainable in this life or in life after death? Can the reduction of moral philosophy to the determination of how to maximise individual or societal happiness be reconciled with the need to recognise universal and objective moral principles? Should happiness be viewed only as a consequence of the performance of unconditional duties? Speaking of the problems occasioned by the nebulous meaning the term "happiness" can have, Mortimer J. Adler said: "It may be granted that there are in fact many different opinions about what constitutes happiness, but it cannot be admitted that all are equally sound without admitting a complete relativism in moral matters." [3]

Plato identified happiness with an inner peace and harmony in the soul. Socrates understood happiness in relation to virtue. He said "the happy are made happy by the possession of justice and temperance and the miserable by the possession of vice." [4] Aristotle defined happiness as "activity in accordance with virtue." [5] He drew a distinction between intellectual virtue and moral virtue giving greater weight to the latter. He taught that a morally virtuous person finds pleasure in doing good. He held that there existed universal and objective moral truths which give rise to the natural moral law. He said: "There is in nature a common principle of the just and unjust that all people in some way divine [discern], even if they have no association or commerce with each other." [6]

In Christian belief, the desire for happiness is of divine origin: "God has placed it in the human heart in order to draw man to the One who alone can fulfill it...God alone satisfies." [7] Here, the perfection of happiness is arrived at through our entry into eternal life with God in Heaven. However, happiness in this earthly life is attainable to the extent that we model our lives on Jesus Christ and seek to live a virtuous life. This includes obedience to the Ten Commandments and all that they entail. Coupled with this, the Beatitudes "respond to the natural desire for happiness," and they "reveal the goal of human existence, the ultimate end of human acts" — which is to share in God's "own beatitude." [8]

Apart from Bentham's ethical hedonism, there are many other varieties of utilitarian thought, such as Robert Goodwin's rule utilitarianism and Peter Singer's preference utilitarianism. Sometimes utilitarianism is referred to as consequentialism, insofar as actions are to be judged good or bad according to their consequences. Singer says that his brand of utilitarianism differs from its classical form in that "best consequences" are understood "as meaning what, on balance, furthers the interests of those affected, rather than merely what increases pleasure and reduces pain." [9] Having said this, however, Singer adds that if we interpret classical utilitarians like Bentham to have used the terms "pleasure" and "pain" in a broad sense so as to "include achieving what one desired" as a "pleasure" and the reverse as "pain," then "the difference between classical utilitarianism" and his own based on interests "disappears.." [10]

Utilitarianism is a form of materialism in that it is focused on immediacy and efficiency in achieving a form of happiness that is confined to this life only. In conjunction with this, the notion of maximising 'utility' (happiness) is laden with ambiguity. For example, since maximising utility implies a comparison of the value of the utility of all forgone alternatives, then how can there ever be enough time to calculate the total opportunity cost in terms of utility forgone as a consequence of choosing one option in preference to another? Further to this, how do we account for those effects of our actions on societal 'happiness' that we are not aware of?

In pointing to utilitarian ethics as a product of the English Enlightenment, which tended to forget the human element in morality, Professor William K. Kilpatrick said:

-

"It was a sort of debit-credit system of morality in which the rightness or wrongness of acts depended on their usefulness in maintaining a smoothly running social machine. Utilitarianism oiled the cogs of the Industrial Revolution by providing reasonable justifications for child labor, dangerous working conditions, long hours and low wages. For the sake of an abstraction — 'the greatest happiness for the greatest number' — utilitarianism was willing to ignore the real human suffering created by the factory system." [11]

As a moral philosophy, utilitarianism is defective because it postulates that ends justify means and it easily ends up counting as 'pleasurable' and good whatever is the object of desire. To this end, "it tends to regard freedom as the unrestricted exercise of one's self interest," and the satisfaction of one's desires to be "limited only by the proviso that it doesn't infringe the same freedom of others." [13] As such, "it is a receipe for license rather than true liberty and tends to lead to further enslavement as is shown, for example, by the unrestricted use of drugs or alcohol or sexuality." [14]

While we should not minimise the role of motives and circumstances in morality, [15] the morality of the human act depends nevertheless "primarily and fundamentally on the 'object' rationally chosen by the deliberate will." [16] The object of an act refers to its matter — whether or not it is good or evil in itself. In this regard, there exist "moral absolutes" which means that there are objects of human choice which are always and everywhere morally bad. Such actions, referred to as "intrinsically evil," include bestiality and the deliberate killing of babies. In contrast to this, a major objection to utilitarianism is that "it does not allow a statement to the effect that some actions are intrinsically or absolutely good or bad: they are only better or worse than others." [17]

The utilitarian calculus cannot account adequately for the demands of justice, nor does it take into account the nature of desires seeking to be satisfied. For example, the intention to kill an innocent human being is to desire to commit an intrinsically evil act and is thus a disorder of the will. A person intent on performing such an action should be restrained, irrespective of how he or she hopes to increase individual or societal happiness. This, at least, has been a foundational principle of all civilised societies.

Influenced by Joseph Fletcher

Apart from classical utilitarians like Bentham, Singer has also drawn on the ideas of Joseph Fletcher in developing his ethical system. Fletcher, who is regarded as the father of Situation Ethics, was an Episcopalian priest who died in 1991 at the age of 86. In 1960, Fletcher renounced his belief in God but remained a priest because he found the Episcopalian Church useful for advancing his ideas. He was pro-abortion and pro-euthanasia, being an advocate of "mercy-killing" and a member of the board of directors of the Euthanasia Council (now called 'Choice in Dying'). His writings had a futuristic aspect to them in that he spoke approvingly of fetal experimentation and the possibility of manufacturing human beings. Fletcher's wife of 60 years, Forrest Hatfield, worked closely with Margaret Sanger (1883-1966), who was the founder and first president of the International Planned Parenthood Federation, which is now the biggest promoter of abortion world-wide.

Singer draws on Fletcher's personal criterion (which he refers to as 'indicators of personhood') to establish a demarcation line between those human beings who he thinks should be granted the status of personhood and those who should not. In this regard, he lists Fletcher's indicators of personhood as "self-awareness, self-control, a sense of the future, a sense of the past, the capacity to relate to others, concern for others, communication, and curiosity." [18] Interestingly, Singer makes no mention of the fact that Fletcher also included an IQ of greater than 40 as one of his indicators of personhood.

Personhood is Not Inherent in the Human Being

Asserting that personhood is not something inherent to every human being but is contingent on the development of self-consciousness, Singer says: "I propose to use 'person' in the sense of a rational and self-conscious being." [19] On this basis, he distinguishes between two types of members of Homo sapiens — those who are 'persons' and those who are not. He says that an essential qualification for the status of personhood is that a being "be capable of anticipating the future, of having wants and desires for the future." [20] Having thus defined away the personhood of some human beings who for various reasons may not measure up to his criterion of personhood, Singer then boldly asserts that "it is reasonable to say that only a person has a right to life." [21]

Singer's 'New Commandments': Kill the Child if it makes life easier for you

When Singer's utilitarianism is combined with his assertion that personhood is contingent on the possession of exercisable cognitive abilities, what we end up with is a "deathly" cocktail. He holds that the sanctity of life ethic is "terminally ill" in that its claim that all human life has some special dignity or worth "crumbles" when "challenged." He intones that this "traditional ethic" is defended "by bishops and conservative bioethicists...who speak about the intrinsic value of all human life, irrespective of its nature or quality." [22] In place of the sanctity of life ethic, Singer proposes a new one which is replete with five "New Commandments," which he says are necessary alternatives to the five "Old Commandments." The table below shows these two sets of commandments as Singer formulates them: [23]

Singer argues that the selective killing of infants should be permissible, as should other forms of euthanasia and assisted suicide. In regard to the question of killing, he says: "When we consider how serious it is to take a life, we should look, not at the race, sex or species to which that being belongs, but at the characteristics of the individual being killed, for example, its own desires about continuing to live, or the kind of life it is capable of living." [24]

Consistent with his belief that "there could be a person who is not a member of our species," and that "there could also be members of our species who are not persons," [25] Singer asserts that in order "to avoid speciesism we must allow that all beings who are similar in all relevant respects have a similar right to life — and mere membership in our own biological species cannot be a morally relevant criterion for this right." [26] After stating that "there will surely be some nonhuman animals whose lives, by any standard, are more valuable than the lives of some humans," Singer goes on to say: "A chimpanzee, dog, or pig, for instance, will have a higher degree of self — awareness and a greater capacity for meaningful relations with others than a severely retarded infant or someone in a state of advanced senility. So if we base the right to life on these characteristics, we must grant these animals a right to life as good as, or better than, such retarded or senile humans." [27]

In regard to abortion, Singer argues that "an abortion late in pregnancy for the most trivial reasons is hard to condemn unless we also condemn the slaughter of far more developed forms of life for the taste of their flesh." [28] After saying that the fetus is not a person and hence its life "is of no greater value than the life of a nonhuman animal at a similar level of rationality, self-consciousness, awareness, capacity to feel etc," Singer goes on to add that "it must be admitted that these arguments apply to a newborn baby as much as to a fetus." [29] Consistent with this position, Singer asserts that "the grounds for not killing persons do not apply to newborn infants" since "newborn babies cannot see themselves as beings who might or might not have a future." [30]

Regarding Singer's assertion that unborn babies and infants are not persons because they lack certain exercisable cognitive abilities, Professor William May says that this is "fallacious" because "it fails to distinguish between a radical capacity or ability and a developed capacity or ability." Explaining this distinction, Professor May says:

-

"A radical capacity can also be called an active, as distinct from a merely passive, potentiality. An unborn baby or a newborn child, precisely by reason of its membership in the human species, has the radical capacity or active potentiality to discriminate between true and false propositions, to make choices, and to communicate rationally. But in order for the child — unborn or newborn — to exercise this capacity or set of capacities, his radical capacity or active potentiality for engaging in these activities — predictable kinds of behaviour for members of the human species — must be allowed to develop. But it could never develop if it was not there to begin with...Similarly, adult members of the human species may, because of accidents, no longer be capable of actually exercising their capacity or ability to engage in these activities. But this does not mean that they do not have the natural or radical capacity, rooted in their being the kind of beings they are for such activities. They are simply inhibited by disease or accidents from exercising this capacity...

"A human embryo has this active potentiality or radical capacity to develop from within its own resources all it needs to exercise the property or set of properties characteristic of adult members of the species. One can say that the human embryo is a human person with potential; he or she is not merely a potential person. Those, like Tooley and Singer, who require that an entity have exercisable cognitive abilities, recognise that the unborn have the potentiality to engage in cognitive activities. But they regard this as a merely passive potentiality and fail to recognise the crucially significant difference between an active potentiality and a merely passive one." [31]

Singer says that the "present absolute protection of the lives of infants is a distinctively Christian attitude rather than a universal ethical value." He states that "infanticide has been practised in societies ranging geographically from Tahiti to Greenland and varying in culture from the nomadic Australian aborigines to the sophisticated urban communities of ancient Greece or mandarin China." [34] He holds that these cultures "were on good ground" insofar as they "practiced infanticide." [35] Singer even gives a Malthusian twist to his discussion of infanticide. He says that "in the case of infanticide, it is our culture that has something to learn from others, especially now that we, like them, are in a situation where we must limit family size." [36] Obviously, Singer hasn't yet caught up with the now widely acknowledged fact that the only demographic problem in Western countries is declining fertility rates and aging populations.

At times, Singer packages his more controversial propositions in soothing terms. For example, in reference to infanticide he says: "We should certainly put very strict conditions on permissible infanticide; but these restrictions might owe more to the effects of infanticide on others than on the intrinsic wrongness of killing an infant." [37] However, one columnist, George F. Will, caught the barbaric "logic" of Singer's ethical system well in a Newsweek article when he said:

-

"Actually, the logic of his position is that until a baby is capable of self-awareness, there is no controlling reason not to kill it to serve any preference of the parents...During the Senate debate on partial-birth abortion — in which procedure all of a baby except the top of the skull is delivered from the birth canal, then the skull is collapsed — two pro-choice senators were asked: Suppose the baby slips all the way out before the doctor can kill it. Then does it have a right to life? Both senators said no, it was still the mother's choice. To what the senators said, Singer says briskly: 'They're right'." [38]

Indeed, Singer himself admits the arbitrary nature of his position. He says that it is "difficult to say at what age children begin to see themselves as distinct entities existing over time." He adds that "even when we talk with two and three-year-old children, it is usually very difficult to elicit any coherent conception of death, or of the possibility that someone — let alone the child herself — might cease to exist." [39] Nevertheless, Singer still insists that a "line" can be drawn on one side of which the child dies while on the other he lives. He says: "Of course, where rights are at risk, we should err on the side of safety. There is some plausibility in the view that, for legal purposes, since birth provides the only sharp, clear, and easily understood line, the law of homicide should continue to apply immediately after birth." However, he follows up this statement by saying: "Since this is an argument at the level of public policy and the law, it is quite compatible with the view that, on purely ethical grounds, the killing of a newborn infant is not comparable to the killing of an older child or adult." [40] Then, to make provision for those parents whose "preference" is that their disabled child be murdered, Singer says: "It is, however, worth considering another possibility: that there should be at least some circumstances in which a full legal right to life comes into force not at birth, but only a short time after birth — perhaps a month." [41]

Note, how in the last sentence quoted above, Singer speaks only of infants acquiring a "legal right to life," thereby denying that they possess an inalienable right to life. Singer cannot grant any infant an inalienable right to life since he has already defined all infants as non-persons and asserted that "it is reasonable to say that only a person has a right to life." [42]

In arguing for the right of parents and doctors to kill handicapped infants, Singer offers a rather specious reply to the charge that the presence of such licensed killers in a given society would greatly threathen the sense of security felt citizens thus reducing their "total amount of happiness." He says: "[No] one capable of understanding what is happening when a newborn baby is killed could feel threatened by a policy that gave less protection to the newborn than to adults. In this respect Bentham was right to describe infanticide as 'of a nature not to give the slightest inquietude to the most timid imagination.' Once we are old enough to comprehend the policy, we are too old to be threatened by it." [43]

In is meanderings through the thickets of evil abstraction, Singer fails to account for the fact that many people know and feel themselves so bound in solidarity to their handicapped brothers and sisters as to feel great 'pain" and anguish at even the suggestion that disabled infants be put to death.

Nazism Revisited

It is interesting to note that many of Singer's more notorious proposals are directed at severely disabled children since this was also the group the Nazis first targeted for euthanasia. Singer rejects any suggestion that his ethical system would have sat comfortably with the Nazi tyrants. In arguing that his pro-euthanasia position is different in essence to its Nazi counterpart, Singer says: "The Nazi 'euthanasia' program was not 'euthanasia' at all. It did not seek to provide a good death for human beings who were leading a miserable life. It was aimed at improving the quality of the Volk and eliminating the burden of caring for 'social ballast' and feeding 'useless' mouths." [44] The first thing to note about Singer's statement here is that he does not condemn the Nazi euthanasia program per se, but rather he faults it only on the motivation he believes inspired it.

The Nazi euthanasia program is partly accounted for by the fact that Singer-like utilitarian ideas began to gain currency in Germany during the early decades of the 20th century. In 1920, well before Hitler came to power in Germany, a very influential book titled Permission to Destroy Life Unworthy of Life was published. Co-authored by Karl Binding, a law professor, and Alfred Hoche, a physician, this work asserted that killing certain categories of people was a form of compassionate and "healing treatment." Regarding the influence of Binding's and Hoche's work, as well as the section following on Hitler and Baby Knauer, I will be draw heavily on an excellent article by Wesley J. Smith titled Peter Singer Gets A Chair available at www.frontpagemag.com/archives/academia/smith10-22-98.htm.

Those deemed eligible for the "compassionate treatment" Binding and Hoche wanted to mete out to them included the terminally ill and the cognitively disabled. The first category mentioned here, the terminally ill, are the category for whom Singer would legalise voluntary euthanasia. The second category, the cognitively disabled, are those Singer has defined as "non-persons," the killing of whom is "very often...not wrong at all." [45]

Binding and Hoche based their advocacy of euthanasia on the perceived misery of the mentally disabled, as well as on the costs to their families and society of looking after them — something which is echoed in Singer's utilitarian premise that it should be permissible to kill "non-persons" whose lives are deemed "not worth living," and whose death will lead to an increase in the "total amount of happiness."

The publication of Permission to Destroy Life Unworthy of Life sparked discussion among the German intelligentsia as a result of which pro-euthanasia ideas which were once regarded as abhorrent now began to win greater acceptance. Then a 1925 survey of German parents with mentally disabled children revealed that 74 percent of them would have agreed to the painless killing of their children. Hence, when the Nazis looked for the right moment to begin implementing their euthanasia program, an atmosphere sympathetic to it already existed in consequence of the prior dissemination of Singer-like utilitarian ideas.

One of the first people murdered in the Nazi euthanasia program was a child named Baby Knauer, who in 1938 or 1939 was born blind with one arm and one leg missing. Baby Knauer's father felt unable to cope with his disabled son, so he wrote to Hitler seeking permission to have the child put to death. Seeing in this request the opportunity to launch his euthanasia program, Hitler sent Dr. Karl Rudolph Brandt to examine Baby Knauer. Brandt, who at Nuremberg was condemned to death for crimes against humanity, had been given instructions that if Baby Knauer was as disabled as his father made out, then doctors could kill him. Subsequently, Brandt witnessed the killing of Baby Knauer and reported back to Hitler. This incident convinced Hitler that the time was right to introduce his euthanasia program. Thus, in 1939, he sent a note to chancellery officials extending "the authority of physicians" so that "a mercy death may be granted to patients who according to human judgement are incurably ill." [46]

The justification that was used to murder Baby Knauer is essentially the same as Singer uses when arguing that parents should have the right to have their disabled children put to death so that they themselves and any subsequent children they may have might experience an increase in "the total amount of happiness."

Concluding Remarks: From Atheism to Bestiality

A fundamental cause of radical differences in ethical perceptions is that different ethical systems have different starting points — which is to say, they differ in fundamental assumptions. The starting assumptions in any chain of reasoning determine its character and its conclusions. In this regard, all ethical systems rely on a particular anthropology which dictates its line of development.

Christian anthropology holds that God created man in his own image and likeness, that he endowed him with freedom and intelligence, and that he appointed him steward over the rest of physical creation. [47] Being so constituted, human beings are able to know the difference between good and evil and to choose between them. The dignity of the human person lies in his ability to choose the good and the institutions and laws of society should assist him in doing so. In consequence of all this, the human person is the subject of inalienable human rights and corresponding duties. First among those rights is the right to life itself. This right to life of all innocent human beings must be guaranteed at law since it is inherent to the nature of the human person and not conferred by society.

In his encyclical Evangelium Vitae (Gospel of Life), Pope John Paul II said: "By living 'as if God does not exist,' man not only loses sight of the mystery of God, but also of the mystery of the world and the mystery of his own being" (n. 22) He added that "the eclipse of the sense of God and of man inevitably leads to a practical materialism, which breeds individualism, utilitarianism and hedonism" (n. 23). In this, said Pope John Paul, "we see the permanent validity of the words of the Apostle: 'And since they did not see fit to acknowledge God, God gave them up to a base mind and to improper conduct' (Rom 1:28)" (ibid.)

Singer underpins his ethical system with an atheistic anthropology in which he asserts that there is no significant difference between human beings and animals such as baboons and pigs. In publicly declaring his atheism, he says: "I don't believe in the existence of God, so I also reject the idea that each human being is a creature of God. It's as simple as that." [48] In line with this, he accuses "the Judeo-Christian tradition" of having "an unjustifiable bias in favour of human beings qua human beings." [49] He says "the fact that animals are not members of our species is, in itself, no more morally relevant than the fact that a human being is not a member of my race or not a member of my sex." [50]

Singer says that "we should reject the doctrine that places the lives of members of our species above the lives of members of other species," adding that "some members of other species are persons: some members of our own species are not." [51] Following this proposition through to its logical conclusion, Singer asserts that "no objective assessment can support the view that it is always worse to kill members of our species who are not persons than members of other species who are." [52]

Given Singer's starting points, it is not surprising to find that in a March 31, 2001 article in the Sydney Morning Herald titled "Animal-Sex Philosopher Brings Out The Beast In The Americans," Singer is quoted as having stated at the time that sex with animals "is not an offence to our status and dignity as human beings." The article was reporting on a favourable review Singer had written of a book titled Dearest Pet by Midas Dekker which condoned bestiality. The article said that Singer speculates that the reason why most people have a revulsion of bestiality "stems from the Judeo-Christian view of a gulf separating humans from animals."

Being rooted in atheistic perceptions of reality, Singer's ethical system is incapable of defending human dignity. His defense of infanticide and bestiality serves well to illustrate the truth of the statement commonly attributed to Dostoevsky: "If God does not exist, everything is permissible." While this sentence does not, to my knowledge, appear in any of Dostoevsky's novels that have been translated into English, it can nevertheless be regarded as an accurate summation of the belief held by Ivan Karamazov in the early chapters of The Brothers Karamazov where he pretends to conclude that there is no God. While he does not speak directly the sentence quoted above, he does however assert in several places that without God "everything is lawful." Equally insightful, in another place he says: "If there is no immortality, there is no virtue."

Despite the many nuances he introduces into his work to distinguish it from classical utilitarianism, Singer's atheistic system is for all practical purposes just another form of "ethical hedonism."

NOTES:

[1] Cited by Mortimer J. Adler in The Great Ideas: A Lexicon of Western Thought, Macmillian Publishing Company, New York, 1992, p. 300.

[2] Jeremy Bentham, see entry under "Bentham" in The Concise Encyclopedia of Western Philosophy & Philosophers, edited by J.O. Urmason & Jonathan Ree, Routledge, London, 1991, p. 42.

[3] Mortimer J. Adler, The Great Ideas, op.cit. p. 298.

[4] Socrates, cited by Mortimer Adler in The Great Ideas, op.cit. p. 300.

[5] Aristotle, cited by Mortimer Adler in The Great Ideas, op.cit. p. 302.

[6] Aristotle, On Rhetoric, Book 1, Chapter 13.

[7] Cathecism of the Catholic Church (CCC), n. 1718.

[8] CCC. nn. 1718-19.

[9] Peter Singer, Writings On An Ethical Life, Fourth Estate, London, 2000, p. 17.

[10] Ibid.

[11] William K. Kilpatrick, Why Johnny Can't Tell Right From Wrong, Simon & Schuster, New York, 1993, p. 132.

[12] Ibid. p. 133

[13] Peter E. Bristow, The Moral Dignity of Man, Four Courts Press, Dublin, 1997, p. 19.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Cf. Pope John Paul II, Veritatis Splendor, n. 80

[16] Ibid. n. 78

[17] Peter E. Bristow, The Moral Dignity of Man, op.cit.. p. 78.

[18] Peter Singer, Writings On An Ethical Life, Fourth Estate, London, 2000, p. 128.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid. p. 323

[21] Ibid. p. 218

[22] Peter Singer, Writings On An Ethical Life. op. cit. pp. 167-168

[23] Ibid. pp. 211-222

[24] Ibid. p. xv.

[25] Ibid. p. 128.

[26] Ibid. p. 44.

[27] Ibid. pp. 44-45

[28] Ibid. p. 177

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid. p. 161-62

[31] Professor William E. May, Catholic Bioethics and the Gift of Human Life, Second Edition, Our Sunday Visitor, Indiana, 2008, p. 176.

[32] Peter Singer, Writings On An Ethical Life, op.cit. p. 189-91

[33] Ibid. p. 193

[34] Ibid. p. 163

[35] Ibid. p. 229

[36] Ibid. p. 209

[37] Ibid. p. 164

[38] Newsweek, September 13, 1999, Vol. 134, Issue 11, pp. 80-82.

[39] Peter Singer, Writings On An Ethical Life, op. cit. p. 162.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Ibid. pp. 162-63

[42] Ibid. p. 218

[43] Ibid. 161-62

[44] Ibid. p. 202.

[45] Peter Singer, Writings On An Ethical Life, op. cit. p. 193

[46] Cf. John E. Gardella, M.D., The Cost Effectiveness of Killing: An Overview of Nazi Euthanasia (Medical Sentinel 4, no. 4, July/August 1999, pp. 132-35.

[47] Cf. Gen 1:26-31; Blessed Pope John XXIII, Pacem in Terris, n. 3.

[48] Peter Singer, Writings On An Ethical Life, op. cit. p. 320.

[49] Ibid.

[50] Ibid. p. 326

[51] Peter Singer, Practical Ethics (Second Edition), Cambridge University Press, 1993, p. 117.

[52] Ibid.

© Eamonn Keane

The views expressed by RenewAmerica columnists are their own and do not necessarily reflect the position of RenewAmerica or its affiliates.

(See RenewAmerica's publishing standards.)