The one and the many versus multiculturalism

A brief history of conservatism: Part 10

Fred Hutchison, RenewAmerica analyst

Originally published March 11, 2008

Originally published March 11, 2008

In our journey through history, we have reached the culture war of the twentieth century that began in the 1920's and accelerated during the countercultural revolution of the late sixties and the sexual revolution of the seventies. The remaining installments of A Brief History of Conservatism will deal mainly with the postmodern era.

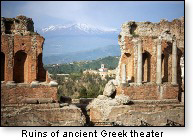

Ancient foundations of Western civilization are being destroyed by the contemporary culture. In order to understand the old foundations of civilization and culture that are now threatened by the multiculturalists, we are obliged to make one more brief visit to Ancient Greece and to the High Middle Ages.

Ideas have consequences

The culture war has deep philosophical roots. Ideas have consequences, according to cultural historian Richard Weaver (1910-1963).

No ideas played a more important role in the rise of the West than two interlocking concepts: (1) "universals and particulars," and (2) "the one and the many." The West provided satisfying solutions to these intellectual dilemmas in the 12th and 13th centuries – and was the only civilization to do so. As we shall see, the Christian doctrine of the Trinity provided the key to the solution of these paradoxes.

Just as these two foundational ideas were essential to the rise of the West, the rejection of these ideas has led to the decline of Western culture.

Universals and particulars

Plato said that universals have independent existence – and that particulars are shadowy and inferior versions of universals. Aristotle said that universals subsist in particulars, but have no independent existence apart from particulars. The Greeks were not able to solve this problem and therefore lacked an essential foundation that Christian Europe enjoyed.

Plato said that universals have independent existence – and that particulars are shadowy and inferior versions of universals. Aristotle said that universals subsist in particulars, but have no independent existence apart from particulars. The Greeks were not able to solve this problem and therefore lacked an essential foundation that Christian Europe enjoyed.

Universals are truths, laws, archetypes, paradigms, and forms that are everlasting, unchanging, ubiquitous, and essential – that is to say, they are the same at every time and in every place and are necessary truths in all cases. The best known example of universals is the universal moral law. Particulars are individual things that are unique to the time and place. A person, a dog, a tree, and a rock are particulars. A detailed irreducible concept is a particular.

The brilliance and resilience of Europe

The Greek philosophers left the riddle of universals and particulars unresolved. That may be why the classical period of Athens was so brief. It was a time of glorious cultural ferment that lasted only about 50 years. The classical Greeks were amazingly intelligent and talented, but they lacked a center that would hold them together.

In contrast, the vigorous development of European culture lasted from 1050-1800 A.D., including four successive eras of cultural development and flowering. Europe did not have one Renaissance – it had four of them. The brilliance and resilience of European civilization did not come from the strength, wisdom, or talent of its men, but from the foundations upon which they built and the faith they embraced.

Wrestling with ideas

The scholastic philosophers in Europe during the 12th and 13th centuries continued the debate that the Greeks began. The first generation of scholastic philosophers were disciples of Saint Anselm (1033-1109 A.D.). The philosophers argued that universals have independent existence, a view that they called Realism.

The Realists had to debate with non-realist philosophers and with extreme Realists who were out of balance. They went through a turbulent period of wrestling with ideas and sifting the bad ideas from the good. Heroic energies were devoted to debating about ideas so that the right foundations for truth would be laid.

The intellectual dynamo in which these special men pursued truth is exactly opposite the intellectual lassitude of the postmodern university, where the scholars no longer believe that one idea is intrinsically superior to another idea.

Intellectual imperialism

Intellectual imperialism

Early in the game, the Realists had to face a proud and tough opponent who practiced intellectual imperialism, namely Peter Abelard (1079-1142). He was a champion debater and a popular celebrity with a cult following. Abelard was a Conceptualist, meaning he believed that universals only exist as concepts.

Civilization can be threatened from many directions. Abelard was the prototype of the proud intellectual who is destructive to culture, because he exalts the mind beyond its proper jurisdiction within the whole of life. He recognized universals as concepts, because concepts were within the realm of his intellectual mastery. He could not tolerate an independent existence for universals, because that would place them outside his understanding and control. He was an intellectual control freak.

Modern science follows Abelard's pattern of epistemological imperialism. (Epistemology is about what we can know and how we can know it.) Epistemological imperialism can be summarized in these sweeping claims: "We are the initiated elite. We alone have the key to knowledge. No other kind of knowledge is valid. Our special knowledge enables us to eventually acquire all knowledge about all things. Nothing exists that we cannot eventually learn about and master. If it is outside the competence of our kind of knowledge, it doesn't exist."

To the extent that the modern science establishment believes and promotes these utopian myths, science becomes destructive to the human soul and to Western culture. Two contemporary examples: (1) the science establishment refuses to listen to criticism from outside the establishment, or to dissenting mavericks inside the establishment; and (2) certain researchers of the brain claim that reason, consciousness, and free will are illusions; they feel that if their methods cannot find it, it must not exist.

A Logocentric world

Roscelin of Compiegne was Abelard's teacher and was a Nominalist who claimed that universals exist only as names. William of Occam was a famous 14th century Nominalist. Postmodern scholars are Nominalists, because they insist that words are arbitrary signs and are empty of meaning. Nominalism often leads to a poisoned skepticism and subsequently to cynicism, nihilism, and despair.

Roscelin of Compiegne was Abelard's teacher and was a Nominalist who claimed that universals exist only as names. William of Occam was a famous 14th century Nominalist. Postmodern scholars are Nominalists, because they insist that words are arbitrary signs and are empty of meaning. Nominalism often leads to a poisoned skepticism and subsequently to cynicism, nihilism, and despair.

In contrast, Realists are "Logocentric" (word-centered, or reason centered). The term was coined by postmodern philosophers to refer to a traditional Western belief in a "metaphysical presence" or a "transcendence signified." Jacques Derrida used the term to explain what it was about Western culture he wanted to destroy. I use the term in the sense of how philosophical Realism applies to words.

Logocentric Realists disagree with the Nominalist belief that words are merely arbitrary signs. They believe that words: (1) carry meaning, and (2) have an independent existence – just as universals do.

Words are not just names of things – they are things. Poet W. H. Auden sometimes asked young aspiring poets why they wanted to be a poet. If a young man viewed poetry as a means of getting out a message, Auden saw no hope for that man as a poet. But if the young man loved to linger among words and listen to what the words are saying to each other, Auden recognized a promising poet. (This paragraph was derived from a Mars Hill Audio interview with Scott Kerns, author of Compass of Affection.)

True poetry is possible in a Logocentric world, but is impossible in a Nominalist world. If words are real things, the poet is an oracle of what the words are saying – not what he is saying. As part of the creation, words bear messages from the Creator and the creation. If words are mere arbitrary signs, the creation grows silent and man, a creature of words, finds himself exiled in a silent, alien world.

In contrast, the scriptures tell us the world is filled with declarative voices coming from heaven and from nature. "The heavens declare the glory of God, and the firmament shows His handiwork. Day unto day utters speech, and night unto night shows knowledge. There is no speech nor language where their voice is not heard." (Psalms 19:1-3).

A friend of mine with a gigantic personal library told me that books have souls. Such Realist beliefs are life nourishing – in stark contrast to the life-destroying nihilism of nominalism. Realist monks who copied and saved manuscripts in the Dark Ages prevented the extinction of Western civilization by saving the great books of that civilization.

Books can save a perishing civilization because books have souls. Books can revive a crumbling culture like ours because books have souls. One of the books saved by the monks was the Bible, which is a spirit-breathed book. A spirit-breathed book is possible because books have souls.

Laying foundations

Those among the realists who adhered closely to the views of St. Anselm were not far from the solution to the problem of universals and particulars. St. Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274), the greatest of the scholastics, put the finishing touches on the Realist project and crafted the definitive solution.

Aquinas was a moderate Realist. He corrected the extreme wing of Realism that had a platonic tendency to cut universals off from particulars, or to diminish particulars, or to define particulars entirely in terms of universals. He also confuted the Conceptualists and Nominalists.

Aquinas said that universals have independent existence – but also subsist in particulars – thereby giving particulars an essence and meaning. However, particulars have unique details that are more than the mere condensation and expression of universals. This formulation vindicated and enhanced both universals and particulars. Always before, philosophers either emphasized universals at the expense of particulars or particulars at the expense of universals. Now men could live in a complete world, fully furnished with both universals and particulars.

Aquinas said that universals have independent existence – but also subsist in particulars – thereby giving particulars an essence and meaning. However, particulars have unique details that are more than the mere condensation and expression of universals. This formulation vindicated and enhanced both universals and particulars. Always before, philosophers either emphasized universals at the expense of particulars or particulars at the expense of universals. Now men could live in a complete world, fully furnished with both universals and particulars.

Ah, the solution to the age-old riddle clearly and definitively explained at last! The foundation was now solidly laid for the construction of the wondrous edifice of Western culture. A Logocentric society was possible because words could share in the essence of universals without forfeiting their integrity as particulars. The tongue and pen of men were now loosened from their long muteness.

Aquinas' formulation was believable and satisfying to most Christians. Since the Creator is transcendent to the creation, it stands to reason that universals are transcendent to particulars. If the Creator and the creation both truly exist, then both universals and particulars have ontological existence – i.e., they are really "out there." If God's nature and glory are manifested in the creation and the creation is deeply embroidered with a plenitude of particulars, then it stands to reason that universals subsist in particulars. If three particular persons subsist in the one godhead, then it stands to reason that God honors the distinct individuals and particulars of the creation.

Aquinas laid the foundations for a flowering of literature. Four great writers appeared after his death who were equipped with the power of Logocentric words – namely Dante, Chaucer, Petrarch, and Boccaccio. They had a voice that spoke to their own generation and that still speaks to us. As discussed in a prior essay in this series, Petrarch and Boccaccio laid the literary foundations for the Italian Renaissance and trained the first generation of leaders of the Republic of Letters in Florence.

Civilized peasants

Everyone who understood Aquinas' explanation of how the body and blood of Christ are offered universally for all people, yet subsist particularly in the sacramental bread and wine, had a simple sketch in his mind of how Aquinas reconciled universals and particulars. Uneducated peasants who were instructed by their parish priests now had an elemental conception of the solution that eluded the Greek philosophers.

Interestingly, the upsurge of interest in universals and particulars during the 1050-1100 period corresponded with a simultaneous upsurge of interest in the mystery of Christ's presence in the bread and wine. The historians have taught us to remember this era by the benchmark of Romanesque architecture.

Contrary to popular belief, the peasants of Europe were not cut off from the general culture. Medieval men had an organic view of society that included the peasants as a living part of the social organism. Powerful, civilizing ideas filtered down to them through the church – such as a sense of how universals and particulars were to be reconciled.

I fancy that this acculturation of the peasants accounts for the charming, civilized countryside in various places – notably Northern Italy, Southern France, the Rhineland, and the Western Midlands of England. These happy Elysian fields starkly contrast with the hellish wilderness that comprised most of Northern Europe in the tenth century (900-1000 A.D.).

The English West Midland counties of Worcestershire, Shropshire, Warwickshire, and Staffordshire were idealized and affectionately satirized by Tolkien as "The Shire." Hobbits in the Shire were caricatures of merry, eccentric English peasants.

Just as Tolkien could not return to dwell in Worcestershire after being in the Battle of the Somme in World War I, Frodo could not long remain in the Shire after visiting Mount Doom. Just as Tolkien recuperated from trench fever in Staffordshire, Frodo's wound was mended in Rivendell.

The genius of a Trinitarian society

The genius of a Trinitarian society

As we shall see, only a Trinitarian society is likely to settle upon a balanced philosophical realism like that of Anselm and Aquinas. Non-Trinitarian societies are highly unlikely to come to that conclusion. The polytheistic Greeks could not solve the philosophical problem of universals and particulars.

The monotheistic Muslims who rejected the Trinity also loved Aristotle. However, they could not solve the problem of universals and particulars and could not accept the West's solution. Partly as a result, the Muslim Ottoman Empire, which was the chief rival of Europe, began to lose momentum after 1700, while the West accelerated in its development as a great civilization.

As we shall see, Trinitarian Realism and Logocentricity were the basis for the characteristic rationality of the West. It is no accident that the scientific method arose first in Christian Europe.

I shall argue that a Trinitarian society is uniquely compatible with Republics. Only a Republic fully implements the political implications of the Trinity. This goes along with the natural law presuppositions of the founders – that only a Republic is in accord with human nature.

Heresy and confusion about universals

Abelard was tried by the church for the heresy of Sabellianism by the great saint and father to kings and popes, Bernard of Clairvaux. The curious fact that the greatest man in Europe would stoop to personally deal with a clever upstart academic debater gives us a clue as to the vital importance of what was at stake.

Sabellianism is the notion that the three persons of the Trinity are merely three modes or three emanations of the godhead. The Sabellian formulation denies the particularity and personhood of the three divine members of the Trinity. We learn from the teachings of Saint Anselm that Sabellianism is a real heresy because if Christ is not a real person, his death and resurrection would have no effect in securing our eternal salvation.

Abelard's confusion about the Trinity is directly related to his inability to believe in both universals and particulars as real things. Trinitarians can recognize both universals and particulars in philosophy and in nature because they recognize it in the Triune God. The one godhead and the three divine persons is the archetype of universals and particulars. This archetype is implicit in the creation and in the rationality of the human mind. The mind is incomplete unless it is furnished with the conception of universals and particulars. That is one reason why the West is renowned for so many stellar achievements of the intellect and the imagination.

God is universal because he is the Creator and Redeemer of all mankind. He is the object of worship to whom all people may turn. His three persons makes him personal and particular. His incarnation as Jesus of Nazareth, a man, bridges the gap between the transcendent universal and the immanent particular. Trinitarians understand that observable particulars in nature do not contradict the implicit universals in nature, because the three divine persons do not contradict the oneness of the godhead.

God is universal because he is the Creator and Redeemer of all mankind. He is the object of worship to whom all people may turn. His three persons makes him personal and particular. His incarnation as Jesus of Nazareth, a man, bridges the gap between the transcendent universal and the immanent particular. Trinitarians understand that observable particulars in nature do not contradict the implicit universals in nature, because the three divine persons do not contradict the oneness of the godhead.

Abelard stumbled before the mystery of the Trinity. Therefore, he denied the independent reality of universals – as the postmodern multiculturalists do.

The contemporary "Emerging Church," a movement of apostate Evangelicals, slid into Sabellianism, because adherents were too intellectually lazy to carefully teach the Trinity. Therefore, they lost interest in universal truth and engrossed themselves in the fads of the depraved contemporary culture. As they embraced Abelard's heresy, they denied Anselm's and Luther's doctrine of the atonement. This may be happening right now at a mega-church near you!

Reasoning from universals to particulars

Saint Anselm, the father of the scholastic movement, taught his disciples to reason from universals to particulars. He started with universal truths that he received by faith. He said, "I believe so that I may understand." From the universal truths, he formulated presuppositions. In a logical and systematic fashion, he worked down from presuppositions to particulars. This method of deductive reasoning, when correctly performed, is uniquely resistant to logic fallacies.

Deductive reasoning opens the mind to objective rational thought. As one steps outside himself to reason in an objective manner, he can recognize subjective bias in his own thoughts and discipline himself against such biases.

Thanks to Saint Anselm and the scholastic movement, the Western mind was opened to new dimensions of rationality. These heightened powers of reason profoundly enhanced Western philosophy, literature, music, art, architecture, and the military and political arts.

The rise of science

It is no accident that science as a systematic intellectual discipline originated in Western Europe. Many earlier civilizations have produced scientific dilettantes – talented solitary amateurs. The West was the first to produce a critical mass of men with heightened powers of rationality who could collaborate in a systematic way to produce a scientific community that encouraged research and discovery – like the Royal Society in London or the Encyclopedia in Paris.

Many writers who have analyzed the rise of science in the West have noticed that Western men believed that nature conforms to law. The Creator incorporated His design of natural laws into the creation. A belief in natural law and laws of nature comes naturally to those who believe that universals exist and subsist within particulars.

Western man had faith that God's gift of reason permitted the thoughts of the human mind to discover the laws of nature. Aquinas is famous for his optimism that reason and nature have a high level of correspondence. Western man was not afflicted with doubt about this correspondence until he was exposed to the skepticism of Hume and the equivocations of Kant in the late 18th century.

The Trinity and the rise of republics

The problem of universals and particulars is closely related to the problem of "the one and the many" – which is the second founding principle of Western civilization. The third founding principle is the incarnation of Christ – God becoming man and bridging the gap between an infinite God and finite man.

God has one being, but three persons. This is the archetype of the one and the many, a concept that is conducive to the rise of republics.

E pluribus unum, the motto of the American Republic, means "Out of Many, One." It means that Americans recognize the nation as a mysterious union of many individual people. A person has ontological being – that is to say, his personhood is really there. In like manner, the one nation is really there. It is not just a conglomeration or a collective as the Libertarians suppose. E pluribus unum is conceptually similar to the biblical doctrine of the church as one body with many members.

E pluribus unum, the motto of the American Republic, means "Out of Many, One." It means that Americans recognize the nation as a mysterious union of many individual people. A person has ontological being – that is to say, his personhood is really there. In like manner, the one nation is really there. It is not just a conglomeration or a collective as the Libertarians suppose. E pluribus unum is conceptually similar to the biblical doctrine of the church as one body with many members.

Some think that the oneness of the American Republic is just as an idea – as the conceptualists like Abelard might have said. Nominalists (like Roscelin, Occam, and the postmodern skeptics) think that the "one" is just an arbitrary name. It takes a Trinitarian Realist to believe in the authentic existence of the nation as a oneness that emerged from the people.

Those who think that the emergent oneness of the nation is just an idea might have trouble understanding the unabashed patriotism of those who realize that e pluribus unum is more than just an idea. The emotional and spiritual love of that elusive thing we call America could hardly exist apart from a Trinitarian populace. The lump in the throat we get when we pronounce the words "the American Republic" is inconceivable to a postmodern multiculturalist. That which we would die for is nonsense to them.

E pluribus unum versus Libertarianism and socialism

E pluribus unum informs us that the membership and participation in a body politic can honor a healthy individualism. We can be both team players and individualists without contradiction. This is precisely what some Libertarians cannot understand. They insist that the collective must of necessity be a threat to the individual.

Trinitarian wisdom suggests that the socialists have gone off the rails in one direction and Libertarians of a hyper-individualistic kind have gone off the rails in the opposite direction. God designed the world so that the community would enhance the individual and the individual would contribute to the community.

E pluribus unum versus Neoplatonism

E Pluribus Unum reverses the paradigm of Neoplatonism (a syncretism of platonism and pantheism) which posits that the many flows from the one. According to that false paradigm, the many have emanated from the one in inferior individual manifestations. Individuals are inferior precipitated lumps from the emissions of the great platonic One.

Interestingly, scientists are saying that the stars are precipitated lumps from the big bang. Einstein's pantheism upon which his scientific theories were based is conceptually similar to the pantheistic elements of Neoplatonism.

In contrast to Neoplatonism, E Pluribus Unum posits that the one is emanated from the many individual people. The American Republic emerges from the people. First the individual, then the emerging oneness. The result is a healthy balance between individualism and a collective solidarity.

Is not a bottoms-up approach politically unstable? Not for a Trinitarian people. The ordering principle of the one and the many descends from God and is imparted to the people. We can have one nation emerging from the many as long as the God of the one and the many is our Master. In contrast, a collection of mere individualists must fly apart through centrifugal forces.

The Trinity versus tribalism

The Trinity versus tribalism

It is no accident that the Lord's special blessing has long rested upon the American Republic. It is a form of government in accord with His nature.

Such a formulation is almost impossible for a Muslim state because Muslims deny the Trinity. Oneness under Allah must of necessity compel the individual to submit and conform. The authoritarian Muslim rulers must extinguish political individuality. The experiment in democracy in Iraq made no headway until their parliament found an unsteady equilibrium as a confederation of tribes. The individual is submerged in the tribe in such a way as to make Jeffersonian democracy very difficult.

The Teutonic tribes that overran the Roman Empire were Aryan Christian heretics who rejected the Trinity. As long as they remained, Aryans could not get the hang of civilization and retained their tribalism. It was not until Trinitarian Christianity was introduced among the barbarians that tribes gave way to organic feudalism, empires, nations, and cities. Many Medieval cities became little Republics containing elements of democracy.

The Trinity makes possible the extinction of tribes and the birth of Republics. In contrast, postmodern multiculturalism encourages a tribalism that is antithetical to a Republic. If we all dissolve into the tribalism of identity politics, the Republic shall surely perish. The man of principle in politics is obliged to fight with all his might against the cancer of identity politics – the notion that I am entitled because I am black, Hispanic, gay, working class, or female. Are you listening, Hillary and Obama?

Human flourishing

The concept of the one and the many is necessary for full human flourishing. A culture flowers to the extent that both individuals and the community are flourishing.

The one and the many meets two primary needs of every person: (1) every person desires to be special and unique in his own right, and (2) every person desires to be an accepted and cherished member of a community. Every baseball player wants to be a star and also wants to be a team player. A star who is shunned by the team, like Ty Cobb, is not happy. An unnoticed team player is not happy.

The one and the many meets two primary needs of every person: (1) every person desires to be special and unique in his own right, and (2) every person desires to be an accepted and cherished member of a community. Every baseball player wants to be a star and also wants to be a team player. A star who is shunned by the team, like Ty Cobb, is not happy. An unnoticed team player is not happy.

In daily life, we might not want to be a star, but we want to feel special and unique in some way, and we want our friends to recognize and value our specialness. We might not want to be reduced to the tightly interlocking system of a baseball team, but we all want to feel ourselves an accepted member of a family or a business team, a fraternity, a church, or a community. We all have the secret need to be part of something greater than ourselves.

These seemingly conflicting needs are hard to meet apart from a society with a Trinitarian consensus. Life in the American Republic prior to the banishment of the Triune God from the public square and prior to the rise of group-think, political correctness, and tribal identity politics was conducive to both the celebration of the individual and the honoring of the group.

Traditional multiculturalism

Prior to the twentieth century, the West practiced a good form of multiculturalism that was made possible by Trinitarian Realist assumptions. The one and the many can apply to multiple cultures. All the national cultures of Europe were reasonably compatible under the aegis of an overarching Western culture, because all shared the same Trinitarian founding principles. The Christian gentleman was educated in the classics of all the nations of Europe.

However, traditional European multiculturalism cannot be extended to the entire world because the Trinitarian, Realist, and Logocentric founding assumptions of European culture are unique and incompatible with most non-Western cultures. This does not mean that international cultural exchanges cannot be fruitful. It means that traditional European multiculturalism cannot be practiced on a global scale.

The nineteenth-century European powers who had international empires discovered the incompatibility of pagan and Christian cultures. However, when European colonies converted to Christianity and accepted the Trinity, as the Latin American colonies did, they were included in the cultural and intellectual dialog of the European multicultural world.

Destructive multiculturalism

Postmodern multiculturalists irrationally insist that there are no necessary barriers to an international cultural community. The multicultural scholars of comparative religions would have us believe that the differences in the world's religions are superficial and that all the various religions are compatible at the core. This is nonsense, of course. These fuzzy-thinking scholars blur the differences with cloudy metaphors. They typically greet the logical criticisms of their sweeping metaphors with charges of bigotry.

The older Western multiculturalism enshrined reason. Postmodern multiculturalism is based upon a revolt against reason. One has to check one's reasoning faculties at the door to think that Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Animism are fundamentally the same in essence.

Postmodern multiculturalists correctly recognize that traditional Western culture is a barrier to their dream of an international community of cultures. Western Trinitarian rationality, Realism, and Logocentricity stand athwart their internationalist agenda. As a result, they either exclude the West from their multicultural carnival or demonize the West. This is why hatred of the West is one of the passions of American left-wing radicals.

Postmodern multiculturalists correctly recognize that traditional Western culture is a barrier to their dream of an international community of cultures. Western Trinitarian rationality, Realism, and Logocentricity stand athwart their internationalist agenda. As a result, they either exclude the West from their multicultural carnival or demonize the West. This is why hatred of the West is one of the passions of American left-wing radicals.

Postmodern professors who are hired to teach the Western classics teach students to deconstruct the text to find coded messages about the agendas of power of the ruling class – as though Shakespeare was part of an elite conspiracy. In this way, the professors try to neutralize the effect of the Logocentric words of the classics upon the students. Feminist professors warn their students about the "patriarchy" of dead white European males – as though Romeo and Juliet is patriarchal propaganda and the tale of star-crossed young lovers is Shakespeare's clever gambit to seduce and deceive the reader.

Trinitarian creativity

The Trinitarian concepts of universals and particulars are an excellent guide to good and bad creativity. Since universals dwell in particulars, great works of art and literature use particular circumstances to convey universal truth and beauty.

The artist does not create universals – he discovers them. Therefore, he is not a creator like God. However, the artist can be original in how he organizes and communicates the universals.

Each artist is a unique individual and can hardly avoid infusing something of his personal uniqueness into his work. Talents are remarkably unique. There was only one Shakespeare, one Rembrandt, and one Tolstoy.

Great literary classics are saturated with strange idiosyncrasies, yet somehow universals of truth and beauty shine through. Aristotle and Aquinas insisted that particulars are not just vessels for carrying universals, but have independent idiosyncratic features that they called "accidents." The idiosyncrasies of the author are "accidental" features of the author that do not impair him from being a messenger of universals – unless he gets self-absorbed and allows his peculiarities to get in the way.

Dumbing down

The present dumbing down of literature involves a saturation of the reader in rambling particulars and an aversion to universals. As the particulars become divorced from universals, they are drained of meaning and become "dumb" – not in the sense of being stupid, but in the sense of being mute. The Logocentric voice of words is muted and gagged by postmodern writers.

The shelves of what was once my favorite Christian bookstore were eventually gutted of meaty books to make way for fluff and fad books, and a great jumble of Christian bric-a-brac and kitsch. That store, which has since closed, became a metaphor for the dumbing down of the Christian writer.

Bad creativity

Beginning with the Romantic movement in the eighteenth century, a false idea of the artist as creator took root. Artistic genius began to be equated with the divine power of creation. For a time, it had a tremendous stimulative effect on Western culture.

Beginning with the Romantic movement in the eighteenth century, a false idea of the artist as creator took root. Artistic genius began to be equated with the divine power of creation. For a time, it had a tremendous stimulative effect on Western culture.

The idea of the artistic genius as creator was already taken seriously as Gluck, Hayden, and Mozart were inventing classical music. The great compositions of classical music included some of the most beautiful pieces of music ever composed – yet the classical music movement contained within it the seeds of its own destruction. All the works of man – even the most noble, inspired, and refined – are tainted by original sin.

The quality of composition declined in the late 19th century as the originality of creation became valued over the intrinsic merit of the piece. The cult of originality led to the twentieth-century idea of music as self-expression – of which jazz was the most complete exemplar.

After 1920, symphonic music critics began to praise ugly compositions that were disintegrating into chaos, if the piece was original and expressive of the composer. Countercultural dissonance was taken as a sign of originality.

The cult of non-conformity led to a new conformism. New compositions based on 19th century models were regarded as "inauthentic" for the postmodern culture. An old eccentric architect of my acquaintance condemned the design of a beautiful new church because "it is not of this era." I recoiled at this statement of resounding stupidity and decadence. This mindless new cult elbows aside intrinsic merit as it stubbornly insists that art can only be valid as an expression of the contemporary culture.

The cult of originality and freedom have morphed into the prison of cultural determinism. Originality for the sake of originality is not sustainable. The cult of originality has collapsed into a cult of conformity to a culture in chaos – which is the worst of all possible worlds for the arts.

Conclusion

Can Western culture be restored? Yes. What is required is a radical renunciation of the cults of modernism and postmodernism. To do this, we must learn to accept persecution.

If you reject the notion that all religions are essentially the same, or that Romeo and Juliet was written as conspiracy of the patriarchal power elite, the demented post-modern scholars will persecute you if they can. If you told my grizzled old architect friend that the new church is beautiful, and that denouncing it on the grounds that it is not modern is mindless cult thinking – you would have a tremendous battle on your hands. This decadent culture is perishing, but the denizens of the culture will go out fighting. They are loyal to the demons that torment them.

If you reject the notion that all religions are essentially the same, or that Romeo and Juliet was written as conspiracy of the patriarchal power elite, the demented post-modern scholars will persecute you if they can. If you told my grizzled old architect friend that the new church is beautiful, and that denouncing it on the grounds that it is not modern is mindless cult thinking – you would have a tremendous battle on your hands. This decadent culture is perishing, but the denizens of the culture will go out fighting. They are loyal to the demons that torment them.

Once we have renounced a false and wicked culture, let us lay again the foundations of a true culture, which was laid in the 12th and 13th centuries. Let us look to a grounded Realism that vindicates both universals and particulars. Let us honor the one and the many. Let us listen to Logocentric words once more. Let us honor artistic creation solely on its intrinsic values of beauty, harmony, meaning, and humanity.

"Those from among you will rebuild the ancient ruins; You will raise up the age-old foundations; And you will be called the repairer of the breach, the restorer of the streets in which to dwell." (Isaiah 55:12)

A message from Stephen Stone, President, RenewAmerica

A message from Stephen Stone, President, RenewAmerica

I first became acquainted with Fred Hutchison in December 2003, when he contacted me about an article he was interested in writing for RenewAmerica about Alan Keyes. From that auspicious moment until God took him a little more than six years later, we published over 200 of Fred's incomparable essays — usually on some vital aspect of the modern "culture war," written with wit and disarming logic from Fred's brilliant perspective of history, philosophy, science, and scripture.

It was obvious to me from the beginning that Fred was in a class by himself among American conservative writers, and I was honored to feature his insights at RA.

I greatly miss Fred, who died of a brain tumor on August 10, 2010. What a gentle — yet profoundly powerful — voice of reason and godly truth! I'm delighted to see his remarkable essays on the history of conservatism brought together in a masterfully-edited volume by Julie Klusty. Restoring History is a wonderful tribute to a truly great man.

The book is available at Amazon.com.

© Fred Hutchison

October 31, 2013

Originally published March 11, 2008

Originally published March 11, 2008In our journey through history, we have reached the culture war of the twentieth century that began in the 1920's and accelerated during the countercultural revolution of the late sixties and the sexual revolution of the seventies. The remaining installments of A Brief History of Conservatism will deal mainly with the postmodern era.

Ancient foundations of Western civilization are being destroyed by the contemporary culture. In order to understand the old foundations of civilization and culture that are now threatened by the multiculturalists, we are obliged to make one more brief visit to Ancient Greece and to the High Middle Ages.

Ideas have consequences

The culture war has deep philosophical roots. Ideas have consequences, according to cultural historian Richard Weaver (1910-1963).

No ideas played a more important role in the rise of the West than two interlocking concepts: (1) "universals and particulars," and (2) "the one and the many." The West provided satisfying solutions to these intellectual dilemmas in the 12th and 13th centuries – and was the only civilization to do so. As we shall see, the Christian doctrine of the Trinity provided the key to the solution of these paradoxes.

Just as these two foundational ideas were essential to the rise of the West, the rejection of these ideas has led to the decline of Western culture.

Universals and particulars

Plato said that universals have independent existence – and that particulars are shadowy and inferior versions of universals. Aristotle said that universals subsist in particulars, but have no independent existence apart from particulars. The Greeks were not able to solve this problem and therefore lacked an essential foundation that Christian Europe enjoyed.

Plato said that universals have independent existence – and that particulars are shadowy and inferior versions of universals. Aristotle said that universals subsist in particulars, but have no independent existence apart from particulars. The Greeks were not able to solve this problem and therefore lacked an essential foundation that Christian Europe enjoyed.Universals are truths, laws, archetypes, paradigms, and forms that are everlasting, unchanging, ubiquitous, and essential – that is to say, they are the same at every time and in every place and are necessary truths in all cases. The best known example of universals is the universal moral law. Particulars are individual things that are unique to the time and place. A person, a dog, a tree, and a rock are particulars. A detailed irreducible concept is a particular.

The brilliance and resilience of Europe

The Greek philosophers left the riddle of universals and particulars unresolved. That may be why the classical period of Athens was so brief. It was a time of glorious cultural ferment that lasted only about 50 years. The classical Greeks were amazingly intelligent and talented, but they lacked a center that would hold them together.

In contrast, the vigorous development of European culture lasted from 1050-1800 A.D., including four successive eras of cultural development and flowering. Europe did not have one Renaissance – it had four of them. The brilliance and resilience of European civilization did not come from the strength, wisdom, or talent of its men, but from the foundations upon which they built and the faith they embraced.

Wrestling with ideas

The scholastic philosophers in Europe during the 12th and 13th centuries continued the debate that the Greeks began. The first generation of scholastic philosophers were disciples of Saint Anselm (1033-1109 A.D.). The philosophers argued that universals have independent existence, a view that they called Realism.

The Realists had to debate with non-realist philosophers and with extreme Realists who were out of balance. They went through a turbulent period of wrestling with ideas and sifting the bad ideas from the good. Heroic energies were devoted to debating about ideas so that the right foundations for truth would be laid.

The intellectual dynamo in which these special men pursued truth is exactly opposite the intellectual lassitude of the postmodern university, where the scholars no longer believe that one idea is intrinsically superior to another idea.

Intellectual imperialism

Intellectual imperialismEarly in the game, the Realists had to face a proud and tough opponent who practiced intellectual imperialism, namely Peter Abelard (1079-1142). He was a champion debater and a popular celebrity with a cult following. Abelard was a Conceptualist, meaning he believed that universals only exist as concepts.

Civilization can be threatened from many directions. Abelard was the prototype of the proud intellectual who is destructive to culture, because he exalts the mind beyond its proper jurisdiction within the whole of life. He recognized universals as concepts, because concepts were within the realm of his intellectual mastery. He could not tolerate an independent existence for universals, because that would place them outside his understanding and control. He was an intellectual control freak.

Modern science follows Abelard's pattern of epistemological imperialism. (Epistemology is about what we can know and how we can know it.) Epistemological imperialism can be summarized in these sweeping claims: "We are the initiated elite. We alone have the key to knowledge. No other kind of knowledge is valid. Our special knowledge enables us to eventually acquire all knowledge about all things. Nothing exists that we cannot eventually learn about and master. If it is outside the competence of our kind of knowledge, it doesn't exist."

To the extent that the modern science establishment believes and promotes these utopian myths, science becomes destructive to the human soul and to Western culture. Two contemporary examples: (1) the science establishment refuses to listen to criticism from outside the establishment, or to dissenting mavericks inside the establishment; and (2) certain researchers of the brain claim that reason, consciousness, and free will are illusions; they feel that if their methods cannot find it, it must not exist.

A Logocentric world

Roscelin of Compiegne was Abelard's teacher and was a Nominalist who claimed that universals exist only as names. William of Occam was a famous 14th century Nominalist. Postmodern scholars are Nominalists, because they insist that words are arbitrary signs and are empty of meaning. Nominalism often leads to a poisoned skepticism and subsequently to cynicism, nihilism, and despair.

Roscelin of Compiegne was Abelard's teacher and was a Nominalist who claimed that universals exist only as names. William of Occam was a famous 14th century Nominalist. Postmodern scholars are Nominalists, because they insist that words are arbitrary signs and are empty of meaning. Nominalism often leads to a poisoned skepticism and subsequently to cynicism, nihilism, and despair.In contrast, Realists are "Logocentric" (word-centered, or reason centered). The term was coined by postmodern philosophers to refer to a traditional Western belief in a "metaphysical presence" or a "transcendence signified." Jacques Derrida used the term to explain what it was about Western culture he wanted to destroy. I use the term in the sense of how philosophical Realism applies to words.

Logocentric Realists disagree with the Nominalist belief that words are merely arbitrary signs. They believe that words: (1) carry meaning, and (2) have an independent existence – just as universals do.

Words are not just names of things – they are things. Poet W. H. Auden sometimes asked young aspiring poets why they wanted to be a poet. If a young man viewed poetry as a means of getting out a message, Auden saw no hope for that man as a poet. But if the young man loved to linger among words and listen to what the words are saying to each other, Auden recognized a promising poet. (This paragraph was derived from a Mars Hill Audio interview with Scott Kerns, author of Compass of Affection.)

True poetry is possible in a Logocentric world, but is impossible in a Nominalist world. If words are real things, the poet is an oracle of what the words are saying – not what he is saying. As part of the creation, words bear messages from the Creator and the creation. If words are mere arbitrary signs, the creation grows silent and man, a creature of words, finds himself exiled in a silent, alien world.

In contrast, the scriptures tell us the world is filled with declarative voices coming from heaven and from nature. "The heavens declare the glory of God, and the firmament shows His handiwork. Day unto day utters speech, and night unto night shows knowledge. There is no speech nor language where their voice is not heard." (Psalms 19:1-3).

A friend of mine with a gigantic personal library told me that books have souls. Such Realist beliefs are life nourishing – in stark contrast to the life-destroying nihilism of nominalism. Realist monks who copied and saved manuscripts in the Dark Ages prevented the extinction of Western civilization by saving the great books of that civilization.

Books can save a perishing civilization because books have souls. Books can revive a crumbling culture like ours because books have souls. One of the books saved by the monks was the Bible, which is a spirit-breathed book. A spirit-breathed book is possible because books have souls.

Laying foundations

Those among the realists who adhered closely to the views of St. Anselm were not far from the solution to the problem of universals and particulars. St. Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274), the greatest of the scholastics, put the finishing touches on the Realist project and crafted the definitive solution.

Aquinas was a moderate Realist. He corrected the extreme wing of Realism that had a platonic tendency to cut universals off from particulars, or to diminish particulars, or to define particulars entirely in terms of universals. He also confuted the Conceptualists and Nominalists.

Aquinas said that universals have independent existence – but also subsist in particulars – thereby giving particulars an essence and meaning. However, particulars have unique details that are more than the mere condensation and expression of universals. This formulation vindicated and enhanced both universals and particulars. Always before, philosophers either emphasized universals at the expense of particulars or particulars at the expense of universals. Now men could live in a complete world, fully furnished with both universals and particulars.

Aquinas said that universals have independent existence – but also subsist in particulars – thereby giving particulars an essence and meaning. However, particulars have unique details that are more than the mere condensation and expression of universals. This formulation vindicated and enhanced both universals and particulars. Always before, philosophers either emphasized universals at the expense of particulars or particulars at the expense of universals. Now men could live in a complete world, fully furnished with both universals and particulars.Ah, the solution to the age-old riddle clearly and definitively explained at last! The foundation was now solidly laid for the construction of the wondrous edifice of Western culture. A Logocentric society was possible because words could share in the essence of universals without forfeiting their integrity as particulars. The tongue and pen of men were now loosened from their long muteness.

Aquinas' formulation was believable and satisfying to most Christians. Since the Creator is transcendent to the creation, it stands to reason that universals are transcendent to particulars. If the Creator and the creation both truly exist, then both universals and particulars have ontological existence – i.e., they are really "out there." If God's nature and glory are manifested in the creation and the creation is deeply embroidered with a plenitude of particulars, then it stands to reason that universals subsist in particulars. If three particular persons subsist in the one godhead, then it stands to reason that God honors the distinct individuals and particulars of the creation.

Aquinas laid the foundations for a flowering of literature. Four great writers appeared after his death who were equipped with the power of Logocentric words – namely Dante, Chaucer, Petrarch, and Boccaccio. They had a voice that spoke to their own generation and that still speaks to us. As discussed in a prior essay in this series, Petrarch and Boccaccio laid the literary foundations for the Italian Renaissance and trained the first generation of leaders of the Republic of Letters in Florence.

Civilized peasants

Everyone who understood Aquinas' explanation of how the body and blood of Christ are offered universally for all people, yet subsist particularly in the sacramental bread and wine, had a simple sketch in his mind of how Aquinas reconciled universals and particulars. Uneducated peasants who were instructed by their parish priests now had an elemental conception of the solution that eluded the Greek philosophers.

Interestingly, the upsurge of interest in universals and particulars during the 1050-1100 period corresponded with a simultaneous upsurge of interest in the mystery of Christ's presence in the bread and wine. The historians have taught us to remember this era by the benchmark of Romanesque architecture.

Contrary to popular belief, the peasants of Europe were not cut off from the general culture. Medieval men had an organic view of society that included the peasants as a living part of the social organism. Powerful, civilizing ideas filtered down to them through the church – such as a sense of how universals and particulars were to be reconciled.

I fancy that this acculturation of the peasants accounts for the charming, civilized countryside in various places – notably Northern Italy, Southern France, the Rhineland, and the Western Midlands of England. These happy Elysian fields starkly contrast with the hellish wilderness that comprised most of Northern Europe in the tenth century (900-1000 A.D.).

The English West Midland counties of Worcestershire, Shropshire, Warwickshire, and Staffordshire were idealized and affectionately satirized by Tolkien as "The Shire." Hobbits in the Shire were caricatures of merry, eccentric English peasants.

Just as Tolkien could not return to dwell in Worcestershire after being in the Battle of the Somme in World War I, Frodo could not long remain in the Shire after visiting Mount Doom. Just as Tolkien recuperated from trench fever in Staffordshire, Frodo's wound was mended in Rivendell.

The genius of a Trinitarian society

The genius of a Trinitarian societyAs we shall see, only a Trinitarian society is likely to settle upon a balanced philosophical realism like that of Anselm and Aquinas. Non-Trinitarian societies are highly unlikely to come to that conclusion. The polytheistic Greeks could not solve the philosophical problem of universals and particulars.

The monotheistic Muslims who rejected the Trinity also loved Aristotle. However, they could not solve the problem of universals and particulars and could not accept the West's solution. Partly as a result, the Muslim Ottoman Empire, which was the chief rival of Europe, began to lose momentum after 1700, while the West accelerated in its development as a great civilization.

As we shall see, Trinitarian Realism and Logocentricity were the basis for the characteristic rationality of the West. It is no accident that the scientific method arose first in Christian Europe.

I shall argue that a Trinitarian society is uniquely compatible with Republics. Only a Republic fully implements the political implications of the Trinity. This goes along with the natural law presuppositions of the founders – that only a Republic is in accord with human nature.

Heresy and confusion about universals

Abelard was tried by the church for the heresy of Sabellianism by the great saint and father to kings and popes, Bernard of Clairvaux. The curious fact that the greatest man in Europe would stoop to personally deal with a clever upstart academic debater gives us a clue as to the vital importance of what was at stake.

Sabellianism is the notion that the three persons of the Trinity are merely three modes or three emanations of the godhead. The Sabellian formulation denies the particularity and personhood of the three divine members of the Trinity. We learn from the teachings of Saint Anselm that Sabellianism is a real heresy because if Christ is not a real person, his death and resurrection would have no effect in securing our eternal salvation.

Abelard's confusion about the Trinity is directly related to his inability to believe in both universals and particulars as real things. Trinitarians can recognize both universals and particulars in philosophy and in nature because they recognize it in the Triune God. The one godhead and the three divine persons is the archetype of universals and particulars. This archetype is implicit in the creation and in the rationality of the human mind. The mind is incomplete unless it is furnished with the conception of universals and particulars. That is one reason why the West is renowned for so many stellar achievements of the intellect and the imagination.

God is universal because he is the Creator and Redeemer of all mankind. He is the object of worship to whom all people may turn. His three persons makes him personal and particular. His incarnation as Jesus of Nazareth, a man, bridges the gap between the transcendent universal and the immanent particular. Trinitarians understand that observable particulars in nature do not contradict the implicit universals in nature, because the three divine persons do not contradict the oneness of the godhead.

God is universal because he is the Creator and Redeemer of all mankind. He is the object of worship to whom all people may turn. His three persons makes him personal and particular. His incarnation as Jesus of Nazareth, a man, bridges the gap between the transcendent universal and the immanent particular. Trinitarians understand that observable particulars in nature do not contradict the implicit universals in nature, because the three divine persons do not contradict the oneness of the godhead.Abelard stumbled before the mystery of the Trinity. Therefore, he denied the independent reality of universals – as the postmodern multiculturalists do.

The contemporary "Emerging Church," a movement of apostate Evangelicals, slid into Sabellianism, because adherents were too intellectually lazy to carefully teach the Trinity. Therefore, they lost interest in universal truth and engrossed themselves in the fads of the depraved contemporary culture. As they embraced Abelard's heresy, they denied Anselm's and Luther's doctrine of the atonement. This may be happening right now at a mega-church near you!

Reasoning from universals to particulars

Saint Anselm, the father of the scholastic movement, taught his disciples to reason from universals to particulars. He started with universal truths that he received by faith. He said, "I believe so that I may understand." From the universal truths, he formulated presuppositions. In a logical and systematic fashion, he worked down from presuppositions to particulars. This method of deductive reasoning, when correctly performed, is uniquely resistant to logic fallacies.

Deductive reasoning opens the mind to objective rational thought. As one steps outside himself to reason in an objective manner, he can recognize subjective bias in his own thoughts and discipline himself against such biases.

Thanks to Saint Anselm and the scholastic movement, the Western mind was opened to new dimensions of rationality. These heightened powers of reason profoundly enhanced Western philosophy, literature, music, art, architecture, and the military and political arts.

The rise of science

It is no accident that science as a systematic intellectual discipline originated in Western Europe. Many earlier civilizations have produced scientific dilettantes – talented solitary amateurs. The West was the first to produce a critical mass of men with heightened powers of rationality who could collaborate in a systematic way to produce a scientific community that encouraged research and discovery – like the Royal Society in London or the Encyclopedia in Paris.

Many writers who have analyzed the rise of science in the West have noticed that Western men believed that nature conforms to law. The Creator incorporated His design of natural laws into the creation. A belief in natural law and laws of nature comes naturally to those who believe that universals exist and subsist within particulars.

Western man had faith that God's gift of reason permitted the thoughts of the human mind to discover the laws of nature. Aquinas is famous for his optimism that reason and nature have a high level of correspondence. Western man was not afflicted with doubt about this correspondence until he was exposed to the skepticism of Hume and the equivocations of Kant in the late 18th century.

The Trinity and the rise of republics

The problem of universals and particulars is closely related to the problem of "the one and the many" – which is the second founding principle of Western civilization. The third founding principle is the incarnation of Christ – God becoming man and bridging the gap between an infinite God and finite man.

God has one being, but three persons. This is the archetype of the one and the many, a concept that is conducive to the rise of republics.

E pluribus unum, the motto of the American Republic, means "Out of Many, One." It means that Americans recognize the nation as a mysterious union of many individual people. A person has ontological being – that is to say, his personhood is really there. In like manner, the one nation is really there. It is not just a conglomeration or a collective as the Libertarians suppose. E pluribus unum is conceptually similar to the biblical doctrine of the church as one body with many members.

E pluribus unum, the motto of the American Republic, means "Out of Many, One." It means that Americans recognize the nation as a mysterious union of many individual people. A person has ontological being – that is to say, his personhood is really there. In like manner, the one nation is really there. It is not just a conglomeration or a collective as the Libertarians suppose. E pluribus unum is conceptually similar to the biblical doctrine of the church as one body with many members.Some think that the oneness of the American Republic is just as an idea – as the conceptualists like Abelard might have said. Nominalists (like Roscelin, Occam, and the postmodern skeptics) think that the "one" is just an arbitrary name. It takes a Trinitarian Realist to believe in the authentic existence of the nation as a oneness that emerged from the people.

Those who think that the emergent oneness of the nation is just an idea might have trouble understanding the unabashed patriotism of those who realize that e pluribus unum is more than just an idea. The emotional and spiritual love of that elusive thing we call America could hardly exist apart from a Trinitarian populace. The lump in the throat we get when we pronounce the words "the American Republic" is inconceivable to a postmodern multiculturalist. That which we would die for is nonsense to them.

E pluribus unum versus Libertarianism and socialism

E pluribus unum informs us that the membership and participation in a body politic can honor a healthy individualism. We can be both team players and individualists without contradiction. This is precisely what some Libertarians cannot understand. They insist that the collective must of necessity be a threat to the individual.

Trinitarian wisdom suggests that the socialists have gone off the rails in one direction and Libertarians of a hyper-individualistic kind have gone off the rails in the opposite direction. God designed the world so that the community would enhance the individual and the individual would contribute to the community.

E pluribus unum versus Neoplatonism

E Pluribus Unum reverses the paradigm of Neoplatonism (a syncretism of platonism and pantheism) which posits that the many flows from the one. According to that false paradigm, the many have emanated from the one in inferior individual manifestations. Individuals are inferior precipitated lumps from the emissions of the great platonic One.

Interestingly, scientists are saying that the stars are precipitated lumps from the big bang. Einstein's pantheism upon which his scientific theories were based is conceptually similar to the pantheistic elements of Neoplatonism.

In contrast to Neoplatonism, E Pluribus Unum posits that the one is emanated from the many individual people. The American Republic emerges from the people. First the individual, then the emerging oneness. The result is a healthy balance between individualism and a collective solidarity.

Is not a bottoms-up approach politically unstable? Not for a Trinitarian people. The ordering principle of the one and the many descends from God and is imparted to the people. We can have one nation emerging from the many as long as the God of the one and the many is our Master. In contrast, a collection of mere individualists must fly apart through centrifugal forces.

The Trinity versus tribalism

The Trinity versus tribalismIt is no accident that the Lord's special blessing has long rested upon the American Republic. It is a form of government in accord with His nature.

Such a formulation is almost impossible for a Muslim state because Muslims deny the Trinity. Oneness under Allah must of necessity compel the individual to submit and conform. The authoritarian Muslim rulers must extinguish political individuality. The experiment in democracy in Iraq made no headway until their parliament found an unsteady equilibrium as a confederation of tribes. The individual is submerged in the tribe in such a way as to make Jeffersonian democracy very difficult.

The Teutonic tribes that overran the Roman Empire were Aryan Christian heretics who rejected the Trinity. As long as they remained, Aryans could not get the hang of civilization and retained their tribalism. It was not until Trinitarian Christianity was introduced among the barbarians that tribes gave way to organic feudalism, empires, nations, and cities. Many Medieval cities became little Republics containing elements of democracy.

The Trinity makes possible the extinction of tribes and the birth of Republics. In contrast, postmodern multiculturalism encourages a tribalism that is antithetical to a Republic. If we all dissolve into the tribalism of identity politics, the Republic shall surely perish. The man of principle in politics is obliged to fight with all his might against the cancer of identity politics – the notion that I am entitled because I am black, Hispanic, gay, working class, or female. Are you listening, Hillary and Obama?

Human flourishing

The concept of the one and the many is necessary for full human flourishing. A culture flowers to the extent that both individuals and the community are flourishing.

The one and the many meets two primary needs of every person: (1) every person desires to be special and unique in his own right, and (2) every person desires to be an accepted and cherished member of a community. Every baseball player wants to be a star and also wants to be a team player. A star who is shunned by the team, like Ty Cobb, is not happy. An unnoticed team player is not happy.

The one and the many meets two primary needs of every person: (1) every person desires to be special and unique in his own right, and (2) every person desires to be an accepted and cherished member of a community. Every baseball player wants to be a star and also wants to be a team player. A star who is shunned by the team, like Ty Cobb, is not happy. An unnoticed team player is not happy.In daily life, we might not want to be a star, but we want to feel special and unique in some way, and we want our friends to recognize and value our specialness. We might not want to be reduced to the tightly interlocking system of a baseball team, but we all want to feel ourselves an accepted member of a family or a business team, a fraternity, a church, or a community. We all have the secret need to be part of something greater than ourselves.

These seemingly conflicting needs are hard to meet apart from a society with a Trinitarian consensus. Life in the American Republic prior to the banishment of the Triune God from the public square and prior to the rise of group-think, political correctness, and tribal identity politics was conducive to both the celebration of the individual and the honoring of the group.

Traditional multiculturalism

Prior to the twentieth century, the West practiced a good form of multiculturalism that was made possible by Trinitarian Realist assumptions. The one and the many can apply to multiple cultures. All the national cultures of Europe were reasonably compatible under the aegis of an overarching Western culture, because all shared the same Trinitarian founding principles. The Christian gentleman was educated in the classics of all the nations of Europe.

However, traditional European multiculturalism cannot be extended to the entire world because the Trinitarian, Realist, and Logocentric founding assumptions of European culture are unique and incompatible with most non-Western cultures. This does not mean that international cultural exchanges cannot be fruitful. It means that traditional European multiculturalism cannot be practiced on a global scale.

The nineteenth-century European powers who had international empires discovered the incompatibility of pagan and Christian cultures. However, when European colonies converted to Christianity and accepted the Trinity, as the Latin American colonies did, they were included in the cultural and intellectual dialog of the European multicultural world.

Destructive multiculturalism

Postmodern multiculturalists irrationally insist that there are no necessary barriers to an international cultural community. The multicultural scholars of comparative religions would have us believe that the differences in the world's religions are superficial and that all the various religions are compatible at the core. This is nonsense, of course. These fuzzy-thinking scholars blur the differences with cloudy metaphors. They typically greet the logical criticisms of their sweeping metaphors with charges of bigotry.

The older Western multiculturalism enshrined reason. Postmodern multiculturalism is based upon a revolt against reason. One has to check one's reasoning faculties at the door to think that Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Animism are fundamentally the same in essence.

Postmodern multiculturalists correctly recognize that traditional Western culture is a barrier to their dream of an international community of cultures. Western Trinitarian rationality, Realism, and Logocentricity stand athwart their internationalist agenda. As a result, they either exclude the West from their multicultural carnival or demonize the West. This is why hatred of the West is one of the passions of American left-wing radicals.

Postmodern multiculturalists correctly recognize that traditional Western culture is a barrier to their dream of an international community of cultures. Western Trinitarian rationality, Realism, and Logocentricity stand athwart their internationalist agenda. As a result, they either exclude the West from their multicultural carnival or demonize the West. This is why hatred of the West is one of the passions of American left-wing radicals.Postmodern professors who are hired to teach the Western classics teach students to deconstruct the text to find coded messages about the agendas of power of the ruling class – as though Shakespeare was part of an elite conspiracy. In this way, the professors try to neutralize the effect of the Logocentric words of the classics upon the students. Feminist professors warn their students about the "patriarchy" of dead white European males – as though Romeo and Juliet is patriarchal propaganda and the tale of star-crossed young lovers is Shakespeare's clever gambit to seduce and deceive the reader.

Trinitarian creativity

The Trinitarian concepts of universals and particulars are an excellent guide to good and bad creativity. Since universals dwell in particulars, great works of art and literature use particular circumstances to convey universal truth and beauty.

The artist does not create universals – he discovers them. Therefore, he is not a creator like God. However, the artist can be original in how he organizes and communicates the universals.

Each artist is a unique individual and can hardly avoid infusing something of his personal uniqueness into his work. Talents are remarkably unique. There was only one Shakespeare, one Rembrandt, and one Tolstoy.

Great literary classics are saturated with strange idiosyncrasies, yet somehow universals of truth and beauty shine through. Aristotle and Aquinas insisted that particulars are not just vessels for carrying universals, but have independent idiosyncratic features that they called "accidents." The idiosyncrasies of the author are "accidental" features of the author that do not impair him from being a messenger of universals – unless he gets self-absorbed and allows his peculiarities to get in the way.

Dumbing down

The present dumbing down of literature involves a saturation of the reader in rambling particulars and an aversion to universals. As the particulars become divorced from universals, they are drained of meaning and become "dumb" – not in the sense of being stupid, but in the sense of being mute. The Logocentric voice of words is muted and gagged by postmodern writers.

The shelves of what was once my favorite Christian bookstore were eventually gutted of meaty books to make way for fluff and fad books, and a great jumble of Christian bric-a-brac and kitsch. That store, which has since closed, became a metaphor for the dumbing down of the Christian writer.

Bad creativity

Beginning with the Romantic movement in the eighteenth century, a false idea of the artist as creator took root. Artistic genius began to be equated with the divine power of creation. For a time, it had a tremendous stimulative effect on Western culture.

Beginning with the Romantic movement in the eighteenth century, a false idea of the artist as creator took root. Artistic genius began to be equated with the divine power of creation. For a time, it had a tremendous stimulative effect on Western culture.The idea of the artistic genius as creator was already taken seriously as Gluck, Hayden, and Mozart were inventing classical music. The great compositions of classical music included some of the most beautiful pieces of music ever composed – yet the classical music movement contained within it the seeds of its own destruction. All the works of man – even the most noble, inspired, and refined – are tainted by original sin.

The quality of composition declined in the late 19th century as the originality of creation became valued over the intrinsic merit of the piece. The cult of originality led to the twentieth-century idea of music as self-expression – of which jazz was the most complete exemplar.

After 1920, symphonic music critics began to praise ugly compositions that were disintegrating into chaos, if the piece was original and expressive of the composer. Countercultural dissonance was taken as a sign of originality.

The cult of non-conformity led to a new conformism. New compositions based on 19th century models were regarded as "inauthentic" for the postmodern culture. An old eccentric architect of my acquaintance condemned the design of a beautiful new church because "it is not of this era." I recoiled at this statement of resounding stupidity and decadence. This mindless new cult elbows aside intrinsic merit as it stubbornly insists that art can only be valid as an expression of the contemporary culture.

The cult of originality and freedom have morphed into the prison of cultural determinism. Originality for the sake of originality is not sustainable. The cult of originality has collapsed into a cult of conformity to a culture in chaos – which is the worst of all possible worlds for the arts.

Conclusion

Can Western culture be restored? Yes. What is required is a radical renunciation of the cults of modernism and postmodernism. To do this, we must learn to accept persecution.

If you reject the notion that all religions are essentially the same, or that Romeo and Juliet was written as conspiracy of the patriarchal power elite, the demented post-modern scholars will persecute you if they can. If you told my grizzled old architect friend that the new church is beautiful, and that denouncing it on the grounds that it is not modern is mindless cult thinking – you would have a tremendous battle on your hands. This decadent culture is perishing, but the denizens of the culture will go out fighting. They are loyal to the demons that torment them.

If you reject the notion that all religions are essentially the same, or that Romeo and Juliet was written as conspiracy of the patriarchal power elite, the demented post-modern scholars will persecute you if they can. If you told my grizzled old architect friend that the new church is beautiful, and that denouncing it on the grounds that it is not modern is mindless cult thinking – you would have a tremendous battle on your hands. This decadent culture is perishing, but the denizens of the culture will go out fighting. They are loyal to the demons that torment them.Once we have renounced a false and wicked culture, let us lay again the foundations of a true culture, which was laid in the 12th and 13th centuries. Let us look to a grounded Realism that vindicates both universals and particulars. Let us honor the one and the many. Let us listen to Logocentric words once more. Let us honor artistic creation solely on its intrinsic values of beauty, harmony, meaning, and humanity.