Stone Washington

“There was never man yet, Christian or Saracen, Tartar or Pagan, who explored so much of the world as Messer Marco.”

~ Rustichello of Pisa

Marco Polo’s 850-year-old grand quest

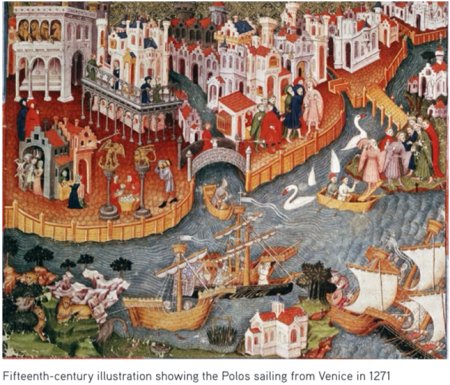

Marco Polo (1254-1324) was celebrated for being the greatest traveler of his time, and in many respects, the greatest traveler who ever lived. Hailing from Venice, Polo officially launched his historic and iconic voyages across the Asian continent in 1271, approximately 850 years ago. It was during this year that he traveled to China to join the company of Kublai Khan, where he operated under his service to carry out a number of important diplomatic missions. As it pertains to possessing a written account, Marco Polo covered more parts of the unknown world than any traveler up to that point in history. The vividly described accounts of his adventures are contained in “The Travels of Marco Polo”, which chronicle his time exploring Asia from 1271 to 1295. The work chronicles the incredible journey to India and across the Silk Road, revealing many of the unique peoples, customs, cultures, and commodities that were traded along the extensive network of trade routes from East to West. Marco Polo inherited his remarkable skills as a traveler by following in the footsteps of his father, Niccolo Polo, and uncle, Maffeo Polo, who were a trusted duo of seasoned merchants in Venice. Due to their extensive travels to Asia, Marco was raised by his mother and hadn’t officially met his father until 1269 when he was already 15 years old. By the time Niccolo and Maffeo returned, Marco’s mother had tragically passed away and Marco had been raised by another of his uncles and aunt. It was from his father and uncle’s teachings that Marco deepened his understanding of mercantile trade.

I initially chose to read The Travels of Marco Polo because I recall not being exposed to the historical importance of Polo as an adventurer, while in grade school. I advise anyone interested in medieval European and ancient Chinese history to read this book and become educated in the unique position that Polo occupied during the era of the warring Khans of the 13th century. It is also a fascinating read for those with a passion for geography and travel. As a scholar of history, I am very pleased with the knowledge gained from reading The Travels and better understanding the legacy of Marco Polo over 800 years later.

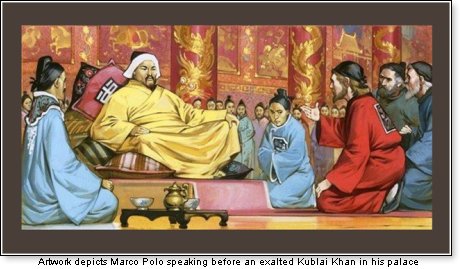

Niccolo and Maffeo had returned from a long voyage, having been sent directly by Chinese ruler Kublai Khan to deliver a special message to the Pope at Acre requesting a hundred Christian men who were well versed in their religion and could “demonstrate the superiority of their own beliefs” (pg. 13). The Polos were dispatched to Acre during an unfortunate time, arriving one year after Pope Clement IV had passed, which left Latin Christendom without a spiritual leader for three years. After some delay returning to Venice, a new Pope, Gregory X, was officially named, and the brothers enlisted a 17-year-old Marco to return to fulfill their quest in Acre. Unable to provide the 100 requested men, Gregory gave the three his blessing and they returned to the East for the next 20 years. By 1292, the Polos return to the West escorted by Arghun Khan of the Levant, and by way of the Malay Straits, with Marco now able to provide an extensive account of Chinese and Peking history.

The grand narrative of the Polos’ adventure concludes upon their arrival to Venice in 1295, with a few verbal tales spoken by Giambattista Ramusio in the years after. The Travels of Marco Polo were written in collaboration with Rustichello of Pisa, an Italian Romance writer whom Polo would encounter after being made a prisoner of war at Genoa in 1298. Polo was presumably released in 1299 and would later pursue a peaceful life as a wealthy merchant, became married, and had three kids. He died in Venice in 1324.

Marco Polo’s exciting life and grand adventure provided the first official European account of Asia, the chronicled experiences of which opened the Western world to a series of new environments, unique ethnic customs, and an exotic array of precious materials, including special fabrics, gunpowder, unique animals, and paper money. The remarkable account of his travels would inspire other legendary explorers, including Christopher Columbus, in addition to his many maps of the places traveled greatly influencing European cartography. With 2021 marking the 850th anniversary of the launch of Polo’s famed quest, I will provide an insight into many of the more significant aspects of the explorer’s riveting continental adventure, highlighting many of the governing network of Mongol Khans who ruled over Asia. I will give specific focus to Kublai Khan who reigned supreme above the other governing khans of his time, and of whom the Polos commanded a great deal of respect from upon their diplomatic collaborations and trade agreements. I will also examine many of the unique tales passed on through Marco Polo’s travels, detailing heroic triumphs of the Christian faith over secular tyranny, epic conflicts between warring rulers, and shadowy military coup vs. direct bouts of invasion to dethrone the governing elite. Most tales are recounted in as vivid detail as the array of exotic places and peoples in which Polo encountered on his journey.

Who were the Mongol Khans?

As depicted throughout The Travels, the Mongol Khans were a group of eastern warlords who reigned supreme over the vast majority of Asia. Each Khan possessed sizeable quantities of resources (including gold, silver, silk, precious gems, and iron), large standing armies, vast naval armadas, and contested control over large swaths of territory. The term Khan denotes an elevated distinction for classifying a military leader or ruler in Central Asia, meaning “Great lord of lords”, similar to the more ancient variant of Khagan (emperor or sovereign). In the Mongolian Empire, Khagan referred to the ruler of the Khans, typically referred to as “the great Khan”, with Kublai Khan being the 5th to ever bear this honorary title and serving as the greatest of the rulers during the time of Marco Polo’s travels.

In the Seljuk Empire, Khans were depicted as the highest class of rulers, outranking maliks (kings) and emirs (princes). Many of the Khans were defined by a title that denoted their territory, such as Barka Khan—lord of a vast part of Tartary to the West; Hulagu, the Khan of the Levantine Tartars; Abaka—Kublai Khan’s brother, Chaghatai and Barak—the Khans of Turkestan of Transoxiana; Baidu, Ghazan, Ahmad, and Arghun—Khans of the Levant (encompassing portions of the Middle East); among others. With many deriving their status from hereditary ties to various Khagans, these Khans were infamous for warring amongst one another often over sibling rivalries, disputes over claims to land ownership, or possession of precious commodities. An example of this is the dispute that took place between Hulagu and Barka Khan, each marching out with their vast forces to meet in battle. After a great loss of life on both sides, Hulagu was declared the ultimate victor. This war prevented anyone from traveling about in Barka’s land, forcing Niccolo and Maffeo to remain in the territory for a year while the dispute was resolved.

Kublai Khan was the son of Chinghiz Khan, and the grandson of the infamous Genghis Khan. Kublai claimed his title as lord over the Tartars by direct imperial lineage and officially began his reign in 1256 AD, after winning the title in competition with his brothers through his impressive prowess and valor, according to Marco Polo. To highlight the Great Khan’s militaristic strength, Polo tells a story of betrayal when Nayan, Kublai’s uncle and vassal, decided to amass his 400,000 horsemen and allied with Kublai’s nephew, Kaidu, who had 100,000 horsemen for rebellion against Kublai. They devised a pincer attack where one would advance on the Great Khan from one direction and the other would advance from the opposite direction.

Prior to the attack, Kublai Khan heard of the coupe and wisely marshalled his own forces, vowing to destroy both of his foes. He was able to assemble 260,000 cavalry and 100,000 infantry, largely made up of civilians in his own immediate neighborhood. This, since many of his primary forces were scattered across the world conducting battle on his behalf, and thus could not be summoned in time. According to Polo, if Kublai possessed all of his forces, they would easily “have been past all reckoning or belief” (pg. 114). Kublai also decided to swiftly target Nayan alone, in order to deny his advantageous position with Nayan, and more easily defeat him in absence of his ally Kaidu. After consulting with his astrologers, who guaranteed his victory, Kublai set out on a twenty-day voyage to find Nayan in a valley beside his forces. Kublai had all of the roads leading to the valley monitored so that he arrived perfectly unseen, while Nayan lay with his wife in a tent, completely unaware.

Without any sentries or guards on watch, Kublai came upon Nayan and his men on a nearby hill, surrounded by a wooden tower of fully armored crossbowmen and archers riding elephants. He assembled thirty squadrons each filled with 10,000 archers, and in front of each were 500 foot-soldiers wielding swords and short pikes. Upon seeing this, Nayan was utterly shocked and wasted no time to quickly assemble his forces and went to battle in what was a bitter and bloody skirmish. Arrows rained throughout the sky, as Nayan, who was a baptized Christian and bore the cross of Christ, drove his forces to clash with Kublai, creating what at the time was the largest battle to date in terms of men and horsemen, according to Marco Polo. But as the battle dragged on, Nayan realized he couldn’t hold out any longer and sought to flee, only for all of his barons and men to be forced to surrender, while Nayan was taken prisoner under Kublai, who later ordered his execution.

Upon this victory, Nayan’s men, who hailed from the four provinces of Kauli, Chorcha, Sikintinju, and Barskol, pledged their fealty to Kublai Khan. Upon witnessing Nayan’s defeat, many Jews, Saracens, and various idolators who did not believe in Christ, openly mocked Nayan as a traitor and jeered at the Christians who were present. The Great Khan would exit in merriment to remain in his capital of Khan-balik, while the prince Kaidu, upon hearing of Nayan’s tragic defeat, was greatly dismayed and abandoned his campaign in fear that the same fate may befall him, and from that time on, was on constant watch against his uncle.

Kublai Khan’s wealth and empire

In describing the city of Khan-balik, in the province of Cathay (North China), where the Great Khan dwelled, Marco Polo did not mince words when explaining how marvelous and regal of a place it was. It received many treasures from India via the Silk Road, including pearls, thousands of cartloads of silk, and various precious stones. There are also a host of female servants and hotel-keepers at the ready. In the center of the city is a gloriously grand palace, with every gateway being guarded by 1,000 guards. He commands a personal guard of 12,000 men called the Keshikten, or “knights and liegemen”, employed not by means of fear, but as a display of his sovereign authority. 3,000 of the men commanded by a captain remain present in the Khan’s palace for 3 days and 3 nights, rotating with another group of 3,000 throughout the year. Kublai Khan has developed a certain suspicion for the people of Cathay and for good reason, due to a certain revolt that had occurred against his authority. This occurred against the authority of a Saracen governor named Ahmad, who commanded the highest level of power and free reign among all who worked under Kublai.

Ahmad abused his power to target and kill anyone he despised, while appointing delinquents in positions of status. He also developed a habit of wooing over any good-looking woman who was unmarried and took his fancy. After a 22-year reign, two men operating under Ahmad’s authority refused to accept his iniquities and abominable deeds any longer and plotted an assassination, while the Great Khan left Khan-balik for the city of Shang-tu. The men were Ch’ien-hu, a Cathayan commander of 1,000 men and whose wife, mother, and daughter had all been violated by Ahmad; and Wan-hu, a commander of 10,000 men. Kublai Khan left the city under the control of Ahmad, while the greater province of Cathay was under the oppressive control of Tarter rulers, having been obtained under the command of Kublai by force. The two commanders channeled the disdain of the Cathayans to their advantage by convincing them to assist in the assassination plot.

In launching their plot, Wan-hu entered the palace by night to seat himself on Kublai’s illuminated throne, while sending for the summons of Ahmad under the guise that Chinghiz, the Khan’s eldest son, had just arrived. They plotted to use Wan-hu as a distraction for Ahmad, while Ch’ien-hu armed with a sword would behead him from the shadows. But the plot was thwarted when a Tartar commander named Kogatai questioned the unorthodox summons made for Ahmad, and arrived at the palace in his place to find Wan-hu on the throne, by whom he shot and killed with an arrow. His followers would seize Ch’ien-hu in the process, while killing many of the ring-leaders among the rebelling Cathayans, who had fearfully retreated from the palace to their homes. Upon the Great Khan’s return, Ahmad and his son’s duplicitous evils are exposed, prompting Kublai’s wrath, and Ahmad’s execution. Kublai had Ahmad’s treasury emptied into his own and threw his body in the street where dogs tore it to pieces, while some of his sons, who also committed wicked acts, were flayed alive.

Reflecting on the imperial reign of the Khans and Marco Polo’s travels

In concluding Part I of my series, the account of Marco Polo’s harrowing travels comprise an important place in geographical studies and East Asian history. No other traveler of his time provides such a unique and vividly described insight into the vast array of peoples, cultures, exotic commodities, and traditions conducted in partially explored and remote parts of the known world. Additionally, The Travels provides an educational break-down of the hierarchical governance of the ruling Khans during the 13th century, granting readers insider information detailing the many titanic rulers (most notably Kublai Khan) in which he, his father Niccolo, and uncle Maffeo encountered in their various journeys. This specialty access and written account of so many extensive travels proved emblematic of how historically important and culturally dynamic of a figure Marco Polo was.

Marco Polo was fortunate to have received such preferential treatment and obtain such high acclaim from Kublai Khan, providing readers of his Travels with a special look into the realm of the Great Khan that most outsiders would not have access to. My focus in Part I is primarily on Marco Polo’s family background, his early beginnings as a novel traveler, the specific period in history that the Polos’ travels occupied, and the governing authority of the Khans over Asia. Part II will focus on more detailed aspects of Marco Polo’s most exemplary accomplishments and highlight what I found to be the most notable destinations during his travels.

The imperial rule of the Khans during Polo’s time helped lay the ground-work for the modern day establishment of China as a global superpower. Kublai Khan, who reigned supreme of all the Khans of his time, notably established the Yuan dynasty with rulership of present-day China, Mongolia, Korea, and nearby territories. His massive influence stretched beyond the Asian continent to gain reverence as the Khagan in the sight of various European (such as Pope Gregory X) and various Middle Eastern leaders. Kublai spent many of his formidable years in battle with neighboring Khans (including many of his own relatives) and supplanting rival dynasties in East Asia, ultimately succeeding in conquering and subsequently uniting all of China following the Mongol conquest of the Song Dynasty in 1279. He would become the first non-Han emperor to achieve this remarkable feat. With China’s meteoric rise as a developed nation in the late 20th century, a growing economic power-house, and rival militaristic threat to the U.S., the Communist Chinese Party (CCP) of modern day has learned many lessons from Kublai Khan’s imperial dominance 850 years ago.

The CCP’s ruthlessness behind their imprisonment and execution of dissidents, such as the Uyghur Muslims, is sharply reminiscent to the oppression of the Cathayan people, who were similarly imprisoned or executed for attempted rebellion against Ahmad’s treachery. And beyond the Cathayans were many different groups of people who were overpowered by the Great Khan’s military might and subject to his jurisdictional reign, forced to serve as vassals of the Mongolian empire. The breadth of Kublai’s militaristic might, as seen on full display when defeating the Christian leader Nayan to thwart his alliance with the forces of his nephew prince, Kaidu, mirrors China’s modern military. might, actively displaying its arsenal and ground troops as a threat to adversaries and as a boast of strength. Neighboring nations with large portions of the public who claim sovereignty apart from China, such as Hong Kong and Taiwan, constantly fall prey to militaristic abuse or threats for intervention by CCP soldiers, which was especially apparent during the Hong Kong protests in the summer of 2019. A similar framework was described throughout Marco Polo’s book when discussing the Great Khan’s vast empire and subjugation of vast numbers of conquered people. Part II will continue beyond the organization of Kublai’s empire and examine other important elements in Marco Polo’s famous travels.

*N.B: This essay is based in part on a synopsis of Marco Polo’s seminal work, The Travels (1300), the reissue edition published by Penguin Classics (September 30th, 1958).

© Stone WashingtonThe views expressed by RenewAmerica columnists are their own and do not necessarily reflect the position of RenewAmerica or its affiliates.